We talked with Veronika Romhany, our current artist in residence, about her work, her experiences in Prague and the political situation in her home city of Budapest.

Agosto Foundation: How has your artistic residence in Prague been going so far? What have you been working on?

Veronika Romhány: Maybe the best way to describe this period is to say that I was searching for the possible ways of synthesizing certain fragments which I have already been working on or thinking of – all those impressions, expectations, prejudices (political, social, personal, artistic etc.) I had already collected before my stay here, and also those impressions I got after coming here. Notes, 3D sketches, half-read books, discussions, small talk – they all come together to create a foggy data set, the raw material which I later start to form. My theme here is to better understand the idea of a flexible personality and its life-strategy, and especially trying to understand more what may have happened in the last two decades in Central Europe, during the era of late-capitalism, and what role fear plays in the loss of identity. Xenophobia is a spreading tendency, and it is a symptom of the collective disappointment with representative democracy.

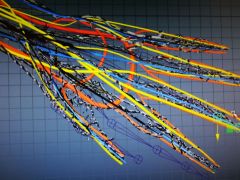

The artistic practice I prefer is something like multi-layered research, if the term “research” can describe this half-conscious, intuition-based method of working. I try to understand and discover the analogies and differences between the two capitals in Central Europe. Of course this is an impossible venture because I am not a sociologist, but rather an artist sensitive to circumstances, with strange interrelations in my head. Since my stay here, I have been working on transforming those visual codes which I already liked to work with previously. In 3D, I want to use more raw material, less aestheticized forms – less rendered images and more of the anti-aesthetics of the working software-space; more machine-like expressions with less theoretical support. Working on the topic of a flexible personality became more of an inner journey – a self-analysis. This situation – the residency program in a foreign country – is quite interesting from this point of view. Flexibility of artistic research? Flexibility of topics? Flexibility in interpersonal relationships? Flexibility as a survival technique? I feel on my skin these questions.

I find the image of a human body as a biomechanical sculpture really interesting; a processor which transforms impressions, feelings, commands, food, liquid – a lot of data and chemistry. This alienation is the key metaphor for my residency here.

Your original intention for the residency was to deepen collaboration with Vera Nimova, the artist. Could you say how Vera Nimova feels in Prague and how it affects her work?

Ha-ha, yes. Seriously, she is going to disappear now – she has started to melt into creative research itself.

She was a persona since the beginning, and as such she functions as a shield. Her existence itself is already ridiculous and embarrassing – I found it interesting for this very reason. She is a shield that will never be identical to its inventor. I was always interested in this hiding/transforming process in literature – a fiction populated by characters – they are always half-invented. I find this process really close to the method of how we live a daily life – that is through our own narrative. It is always deformed to make it acceptable and digestible to ourselves. This distinction is the key in creative processes, and I see analogies between exhibiting an appropriated object in a white cube and this distinctive form of character creation. I was always curious about the internal mental processes, so it was necessary to set a boundary to pretend (or rather represent) a gap. The more I focus on the exact mental process the less I can define this demarcation. I used a phrase during my presentation at the Skautský Institute a few weeks ago and I gave the presentation the title Thick Skin.

So to finally answer the question – this thick skin, this shield is Vera Nimova. And here in Prague, I started to focus on her functionality more, with the result of demolishing her day by day through this analysis. I mean this is more like a transformation, or sublimation. How do I see it now? The defense is already internalized, so the persona itself is no longer as interesting as its function. It is less schizophrenic, more abstract and less focused on gender or identity – like the cyborg of Donna Haraway. A biomechanical sculpture during sublimation. I’m thinking about playing with the word and concept of entropy. How can it be connected to Czech Republic? To Prague? To a flexible personality? I hope it will be visible in the exhibition which will take place at the end of January.

The medium you use a lot, especially as part of your Nimova Project, is 3D animation which you prefer to interpret in relation to “classical” sculpture. Could you say something about 3D animation culture today and its place in contemporary art?

I think that just a few years ago we could have talked about 3D image-making as being still something of an outsider. It was still a bit too futuristic or seemed too scientific (geeky) to be accepted as a real artistic technique. There was also a sense of prejudice, as if it was a mere shadow of cheap game aesthetics around 3D (and now this ugliness, or tackiness, is a key aesthetic trend in itself). This has been changing for a while however; we see interactive games, AI-based interactive games, VR-, AR-based artworks shown in huge biennials, in world-famous galleries, etc. It is only a question of time before this brings about a collective turn in the concept of art. 3D creation in contemporary art relies on accessible technical apparatuses or, more precisely, depends on the individual financial sources. To me, it looks like the youngest child of late-capitalism with an artistic inclination. There is huge potential in 3D-based storytelling, and I think the best advantage of this field is that it’s strongly connected to today’s pop and mainstream culture.

There is a turn now towards open source and user-friendly software, and the introduction of high-quality performance hardware for quite acceptable prices allows more and more people think in virtual three-dimensional space and try out this technique as a possible way of artistic expression. For me, the relationship with 3D graphic software started for a really simple reason: the ability to create a virtual art piece gives the artist a lot of freedom. When you create something, you are already online (more democratic) and your work is already digitized. You need only virtual space (it’s true that you need more and more of this space with time) and you can hold your full collection of works in a few square centimeters. Even if you don’t have a studio, you are still able to create three-dimensional pieces and you are able to animate them. This is magic. For me this ability to create without a wealthy background was crucial. On the other hand, I was also influenced by Fluxus. I believe only in the context in which I can create any kind of artistic representation, and for this reason I can’t see my earlier works as finished, closed objects, but rather as objects with a constant need to be redefined.

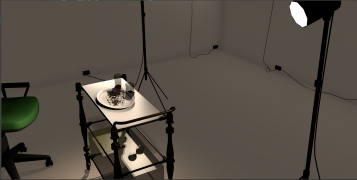

I like to make sculptures in reality, but this practice is more like an instinctive counterpoint to three-dimensional creation. When I do something in 3D software, I need to think totally differently. I am able to recreate or modify the object I create in ANY way, all thanks to the non-destructive workflow. I can really go back in time. When you work with plaster or glue, or paint, or graphite, etc., it is organic and there is no computer in the background; you can hardly ‘undo’ or cancel your exact earlier movements. It feels more like swimming in the open sea instead of a fully equipped and safe swimming pool. I couldn’t imagine my practice without this balance between reality and virtuality.

You had a chance to briefly exhibit your work at a site-specific exhibition in the Colloredo Mansfeld Palace. What does site-specificity mean for you and what connotations, in terms of your work, did the experience of exhibiting at such a historical venue bring?

I would say that for me it was always a bit more interesting to interact somehow with the space than to show a work in a white cube. The rigidity of a clear white space creates a vacuum – in my opinion, this initial state of abstraction is missing from site-specific situations and I like that. In this case, it was a great opportunity for me; I was already working with visual elements connected to power, wealth, and a topic related to the upper class (based on the phrase “Dark Energy”) and it was a great chance to meld these videos into this enigmatic space. During the intervention I used the old silk carpets on the wall to create ghost-like art pieces with the projections – it was a good experience to see the softly added information in the old room already filled with much history. For quite a long time, I’ve intended to use metallic, silky, “rich” materials in videos and sculptures as well, and in the Colloredo Mansfeld Palace I was able to maximize this obsession. Now I feel that I am finally able to step out from the magic of this.

You mention the phrase “Dark Energy.” How would you define such a thing and how does it relate to “power, wealth” and “the upper class”?

I understand Dark Energy as a driving force – a force that is common and mostly unconscious but related to animal instincts: the force that drives a human to win, conquer and occupy everything around. In society, money is a weapon for this and, of course in a more sophisticated way, power as well. I find that the gold-making process and also the chemical transformation of crude oil constitute a great allegory for this primitive, driving force.

Since the rise of Fidesz, the political situation in Hungary has not been favorable to free and politically open art production. How would you evaluate the present state of things for you as a working artist, and how would you compare them to the situation on the Prague art scene?

This is an unfortunate coincidence that my first years after graduating fell into the exact period of the increasing reinforcement of Fidesz. I was really sensitive to these happenings but not radical enough to become politically active. In 2012 and 2013, we needed to digest several changes within the internal cultural politics: important and drastic changes in the education system and the following demonstrations; the disturbing and frightening economic situation of art universities, especially the University of Fine Arts; the infiltration of state influence in decision-making, like the government’s influence in the awarding of scholarships. The feeling was a bit similar to attacking a crystal palace with a hammer. I would say that nearly the whole art scene was vibrating, but not in a good way. It was a bit similar to a small but collective trauma. It was frightening, to be honest. It happened already several years ago, and what do the micro societies and individuals do in such a situation – they try to react and learn from the changes. To be a bit cynical, it seems to me that we are really good at one thing only – surviving. But this also forced the scene to work with the situation – several small, independent organizations and fellowships were created and, also as a statement, OFF Biennial was born. In my case, it forced me to draw up my near future – the paths among which I can choose. I decided to not apply for scholarships, and decided to build a dual life, with a daily job coupled with artistic independence. This freedom was a hugely inspirational advantage in the beginning, but the balance is fragile and for a while I have been feeling the limitations of this pseudo-independency from the art scene. This scholarship is an important step to leave these years behind.

Comparing the connection between the art scene/culture and politics, I see now that what I heard about the Prague scene is true – it remained more independent, but the fact that galleries are disappearing and the looming possibility of a political turn, means that the local scene might have to face something similar. The problem in Hungary is its waterhead – Budapest. Cities with a strong and vibrant cultural life like Brno, Ostrava, or Olomouc can serve as strong barriers to any plans of centralizing power. I think this is an important difference and a great advantage.

Since its political reinvention in 2011, the Hungarian Academy of Arts has been criticized from many corners of the political spectrum. It has been called outdated and rigid. Apart from the rambunctious accusation of not being “sexy enough,” quite concrete and serious accusations have been leveled at it — that it is out of touch with the reality of contemporary art production, that it pays lip service to Orbán’s government, that there are not enough women in important positions … How have artists and gallerists been dealing with this new politicization and bureaucratization, and what is being done to challenge such a state of affairs?

People say that Budapest is really vibrant and interesting now; the underground scene is pulsing, the gentrification is spectacular and Budapest has become a tourist and party destination. Foreigners love it. When I went back for the Christmas holidays after two months spent in Prague (mostly in the center), the first thing I recognized is the huge rate of poverty. This fragmentation of the capital is deeply impressive, and painful. You see parallel worlds – on one hand the propaganda machine, wealth, scandals, concentrations of financial interest – and on the other hand you see incredibly long queues waiting for free hot food distributed by charity organizations and you hear in the news a bit later that there is a new law to legalize free food distribution only for municipalities or church organizations, to the exclusion of NGOs. So the reinvention of MMA comprises a piece of that same puzzle. I believe that the more tension appears in society, the more pressure is put on intellectuals – to react, to protest, to organize. After the first months of “shock” and reactive demonstrations, I see the art scene has had to learn fast and has had to become more self-conscious in order to deal with this complex cultural-political situation. The art space has become much more political with more and more political connotations. The art market hardly exists, so the value of an artwork is rather its moral context.

The OFF Biennale’s aim is to become an independent and democratic interface for artistic discourse – there are collaborations, organizations and also independent and self-organized places like Gólya, MüSzi, or Auróra. I would say that artists and artworkers have learnt to deal with the situation; this, let’s call it “soft cultural dualism” or division, has become an integral part of the art scene. We grapple with this trouble and nearly never talk about MMA anymore – we talk about survival techniques, life-strategies and self-organization, but still talk about the lack of financial sources, the lack of philanthropy, lack of galleries and increasing social immobility – things which also deeply affect the possibilities of the youngest generation of artists.

Vít Bohal and Michal Kindernay