We talked with Miloš Vojtěchovský about his three-part exhibition Census which is currently ongoing at the Display Association for Research and Collective Practice. We also talked about how many steaks and exhausted oceans it takes to commit global ecocide, and where to draw the limits of speculative thought in the face of ecological collapse. And are we really counting on being able to count all of that?

Contemporary life is polluted to its very roots. The human has taken the place of trees and animals, polluted the air and filled all empty spaces. And worse things may still come to pass. This sad and industrious creature might just find and learn to control yet other forces…

Italo Svevo, Confessions of Zeno (1923)

Vít Bohal: One of the objectives of the Speculative Ecologies series is to better understand the potential which lies dormant in the present and which is waiting for its future actualization. Speculation in this regard searches for that which is hidden within the present. In this sense it accepts the material constraints of the present and “speculates” on their possible development moving forward.

I feel that the project Frontiers of Solitude on which you collaborated, was constructed around a similar principle of active speculation — it connected art with research methods and studied the potential of systemic solutions for human and inter-species solidarity. What do you think is the role of art and speculative thought in the age of the Sixth Extinction, advancing ecological crisis and other unprecedented and often accelerating changes, which we are currently experiencing?

Miloš Vojtěchovský: A few years ago, towards the close of the project Frontiers of Solitude, I wrote the fairly “speculative” FOS Manifesto (pdf). But today, I am no longer sure whether I managed to formulate it coherently, and whether it is clear what I intended to achieve: to create a burlesque spoof of my opinions on the real gravity of the situation. Maybe some of it still makes sense? Because the world of written words is exponentially growing thanks to reproductive technologies, I of course have no idea whether anyone has ever even read it. With the universe of human words exploding, there is a proportional decrease of people who pay any attention to the written word, much less read and think about text. There is also an increase in the number of robots and algorithms which upload our words somewhere, parse them, edit, translate, distribute, tweak and maybe even hide them. If there comes about a disturbance, a system collapse, after a few centuries there will again be nothing to read or to eat. And then we can again try to learn to read, write, think and really communicate with each other.

Anyway, I have no idea what such “potential which lies dormant in the present and which is waiting for its future actualization” might consist of. From the perspective of history, it is obvious that the contemporary subjects of history usually cannot grasp the nature of their present, as they are too ensconced in it, and it is not at all easy to come up for a breath and take a look around. We are usually able to understand and experience in depth and in a general fashion only that which draws from our own personal experience, from what we ourselves have lived through; what we learned from literature, science, philosophy, theater, film, meaning everything we call “information,” only makes sense when it resonates with our own personal experiences. Otherwise, they are just empty constructions and phrases — the Veil of Maya, fluttering on the winds of nothingness. If the “information” about the impacts of advancing climate change remain only a topic for expert articles, or news stories on TV and the radio; almost no one would be willing to change or limit their lifestyle, or curb their comforts which oftentimes add to the problem; or even attempt a wider systemic change on the level of society. But when a flood takes your car, a tornado rips off your roof, you will have to think about why that happened and what you might do about it.

One thing which was not discussed in the FOS Manifesto is that art (and other fields as well, of course) is, or can be, like aqua regia: it can dissolve, undermine, deconstruct, unmask facades, the infantilism and emptiness of our civilization built on advertising and marketing design. The vapidness of image surfaces, digital visions, corporate design — these are meticulously and “scientifically” produced, maintained and reconstructed according to the current situation on the economic and political markets. Facades are very powerful and dangerous: they create an illusion and offer an “as if” reality. This is not only the case of computer screens, film screens, or public space, but they have rather become implicit in our thought and action, including my own thought and action … So I consider here the term “speculative” as a tool for identifying these false surfaces. Art, which is able to decouple from the market or consumption and entertainment, allows us to see with “our own eyes” and hear with “our own ears”, and foster a greater degree of resilience and flexibility. This is not necessarily a pleasant or fun endeavor. “Speculative” functions of art can allow us to realize that much of what has been presented to us as law, as a norm or codex, are largely “norms” which have robbed us of our ability to think and maintain a proper degree in things. I for example mean this norm of “endless progress,” growth, the right to hypermobility and the accompanying stakes of the automotive industry, the norm of consuming energy derived from carbon, nuclear fission, etc. Everything changes with time: at the time when these technologies were first discovered they might have been considered “progressive,” maybe even beneficial. Today, this is no longer the case. And there is also a shift in the meaning of “conservative” — it no longer sounds as conservative and unpalatable as it may have just a few years ago.

VB: You say that we are formed by “what we ourselves have lived through. What we learned, acquired from literature, science, philosophy, theater, film,” and so my question is about how the young generation of artists who work in such media reflect on the themes of ecology, climate change, soil erosion, loss of biodiversity, sustainable urbanism. What role does the pedagogical institution play in the framing of the speculative potential which underpins progressive artwork and thought?

MV: What do you mean by “progressive”?

VB: By progressive artwork and thought I simply mean such projects which we would expect from the young, up-and-coming generation of artists ,m projects which process the sometimes hidden, but always widely relevant, themes of the contemporary lived experience in new ways and with the help of new media.

MV: I consider terms such as “progressive” or “conservative” to be treacherous symbolic constructs, and it is necessary to be vigilant and to constantly critique them; they must be revised, deconstructed. This is not easy to do, as they are often lodged deep within our mindset. They constitute the frame for our value system, the mental order in which we grew up and which was taught to us as children. As soon as we critically struggle against similar “paradigmatic” constructs, we are also struggling “against ourselves,” against a part of our identity, or at least certain corners and recesses of our minds. I could find a number of examples, like our relationship to food, our tendencies to make our life easier, the “freeing of man from labor” as they say.

Take food for example: our genetic makeup includes a pattern which tells us that if there is something worth eating around us, we ought to eat it to the fullest. Because who knows when the next opportunity will arise to catch and eat something? Along with the technologies of procuring and preserving food, our nutrition has become one of the detrimental civilizational factors. Overeating — sugars, fats, all these things damage our bodies perhaps more than a little hunger, than a momentary lack of food. We have been used to going hungry since forever, since the Paleolithic as well as the Mesolithic. Between access to food, the stability of the community and the sustainability of the surrounding biotope, access to food and illness played a fundamental role of regulative feedback. Today, a large part of the world population lives in relative plenty, and some paradoxically suffer from an overabundance of food. But such a saturated system is not only bad for our bodies and souls, but also for our environment. The trajectory of apparent benefit pushes us slowly towards collapse, whether this consists in the pillaging of the oceans, or the number of livestock fulfilling the human’s obsessive taste for pork chops and beefsteaks. We selfishly refuse to think and are not willing to admit that the change of weather and the climate is most likely taking us beyond the brink, after which fish, cows, chickens and humans will no longer be able to survive this myopic gluttony, this destructive industriousness. We are afraid of storms, floods, tornadoes, the bark beetle, sharks, lynxes and wolves, but we refuse to admit that the news about the dying out of insects and the erosion of farmland is much more serious. We stupidly assume it as progress when we get more kilometers of highways, more sprawling supermarkets. Perhaps we also live in one such “megahypermarket”? But it can easily go bankrupt.

A little note on the effects of progress on the young generation: I hope that they are better informed than we, the aging and departing generation, were back in our day. They are more resilient than us, we who had planned, celebrated and executed this parade march to the gates of ecocide. Unfortunately, it will be them who will have to face the effects. I just hope they can pry their eyes from their mobile screens and do some radical act which is necessary for change to happen. I am not sure whether they have something to learn from the old generation, something which would help them face their new life conditions in the Anthropocene.

VB: As a former teacher (FaVU, FAMU) you played an active part in the formation of the young generation of artists, and the ecological context has been important to you since at least the 1990s, as we can see from FOS, but also the series of symposia Hermit (1992-1999) which took place at the Plasy monastery …

MV: In retrospect, I am a bit ambivalent about my work at the two mentioned institutions. I won’t comment on the various affairs connected to my work at those art schools. My problems arose from my approach to the institution, rather than from the field itself, the students, or colleagues. Encountering the Brno art school was interesting, and the beginnings at FAMU, when we were setting up and forming the Centre for Audiovisual Studies (which later showed itself to be somewhat of a dissenting department from the current structure of film and photography), was also a positive experience. My experience with the operation and structure of fine art institutions of higher learning was however not altogether optimistic. I am of course partly guilty of this too. But only partly!

As per the Hermit project, I’ve commented on it numerous times, and don’t really have anything much to add. It’s a chapter which was headed to dissolution from the very beginning, and I guess that’s a healthy and good thing. When something is kept alive too long, it can’t turn out very well. It would be interesting to compare Hermit with other then-contemporary events, both at home and abroad, and within the context of the ensuing normalization which started dominating Czech society around the mid-1990s. This autumn, there will apparently be an exhibition and symposium dealing with the theme of the 1990s in Central European culture, so I am looking forward to that.

VB: The Display gallery is currently hosting your three-part exhibition project entitled Census. As Zbyněk Baladrán and Lukáš Likavčan note in their curatorial introduction, the word ‘census’ can be understood as “a qualified approximation and ledger, meaning a tool for grasping and control.” Do you consider the work a critical gesture aimed at the equalization, leveling and dissolution of the lived environment for the benefit of feeding state-owned or monetized databases? Contemporary discourse seems to be very focused on the progressing culture of surveillance afforded by digital tools and the wider digital ecology of the internet …

MV: I named the exhibition Census for a number of reasons: first, in order to fulfill a request that the exhibition must have a name — which is in and of itself a form of pressure, of leveling. Secondly, at the time when I was conceiving the project, Czechia was just undergoing a population census. With the rise of Covid-19, we were furthermore constantly barraged with a flood of graphs, figures, data: how many people were infected that day, that week, how many people are on life support in hospitals, how many ultimately died in hospital. I thought about what such constant addition, subtraction, division and multiplication in fact means. What is this drive to transpose and transcribe the human and reality into numeral values, into data, and why do we seek solace in this numerical flood, while we “drown in numbers”? Does the endless counting also carry with it some less beneficial effects on the citizen, life, economy, health, poetry, or nature? This mode is a bit more complex and metaphorical, so I will try to explain it a bit. It is rather a feeling which I prefer not to rationalize or put into words. But here I must: I assume that the essence of our system, which I consider to be self-destructive, is on a fundamental level comprised of numbers and calculations. And I also believe this wasn’t always the case in all cultures throughout history. So, what have these numbers brought us?

If I remember correctly, in his work The Natural World as a Philosophical Problem (Studies in Phenomenology and Existential Philosophy) (a book which had a profound effect on me when I first read it), Jan Patočka devotes a chapter to numbers and gnoseology. I don’t want to speak phenomenologically here, but rather pragmatically: it seems that numbers have certainly made our lives easier, and that they allow us to basically overcome anything — it seems that this is simply how history progresses, if only for that fact that these are, after all, very "human histories"! The human is considered the pinnacle of Hegelian being. Or so we tell ourselves. Our ability to think and count abstractly predicated on this useful brain capacity — this human, almost divine, Promethean power of thought, prediction, cognitive grasping, this mental and manual ability to use tools — this all seemingly makes the human stand apart from everything around it, and even places it on a pedestal: above the sky, stones, trees, hills, water, animals, vegetables … And maybe this is the reason we deal so callously with our surroundings? But where is it written that we also possess what surrounds us? There is no “natural” right to use the power and energy of animals for our purposes, for our predatory pillaging of resources, oil, the cloning and eating of vegetables, releasing toxins into the air, into the water! The human as an animal species did not get a license to kill — if we disregard pastoral Biblical conceits — but neither did the whales, orcas, lions, microbes, salamanders, beetles, or condors! As soon as any species started behaving like we currently are, this gradually, or in fact quite quickly, brought them to extinction.

It is said that only the human is able to spot relationships and causality in the world, and to learn from its own and others’ mistakes: to calculate what is beneficial for him. But millions of years of evolution on this Earth show how any expression of “selfishness,” of the uncontrolled growth and consumption on the part of one species tending towards exhaustion of resources have quickly placed them in the discard column of the book of life.

But if we manage to somehow negotiate the fact that nature is not an bottomless vending machine, but rather more something like a “commons,” a “shared resource,” and that we must — much like it used to be with the ancient human tribes of the past — share in its bounty carefully, sensitively and conditionally with others, we could draft a new social contract: no longer with Jehova, or any of Gods, but with Nature. Whatever that may be. Then the “prodigal son” could return from this far out psycho-trip and return to its embrace. I know this is utopia. But it is also the prerequisite for a no-longer calculated, but rather resilient, moderate and just mode of being of this one species on Earth. It is most likely utopia indeed, as humanity is certainly not as voluminous in terms of its biomass as, for example, insects, but still the current way of life does not seem compatible with the conditions which this planet has had since the Quaternary. Just like a census, the number and ecological footprint of humans is on the rise, and we are getting beyond the point of negotiating a common strategy which might allow us to endure the changes which we have brought upon ourselves. What you could do on a small island — which the world’s billionaires have recently been doing in the hopes of escaping the consequences of their own opulence — you cannot manage on a planetary scale.

The idea of “Census as a tool for control,” surveillance, management, demographics, statistics, mathematics, social sciences, marketing, politics, etc. is built on the idea that as soon we are able to count something, we will most likely have it under control. This rational, numerical sanctity — calculation, addition, ordering — makes everything into human property. Things and beings lose their autonomy and become a countable module of reality. I don’t mean to imply that science, physics or mathematics are culpable in this, but rather the way we apply science and scientific findings. They become the motor and merit of the economic, monetary system. From the technology of splitting an atom, to the production of artificial materials, fertilizers, to technomedicine which allows us to live longer. We might know how to prolong the human life span, but we don’t know how to care for those who now live longer. They live longer, but are they really alive…?

VB: In your reading, “speculation“ really does seem synonymous with a calculation on the future, largely carried by the technological means of certain particular global players.

MV: You might be thinking of geo-engineering — the idea that we must select a fitting technological fix, and that the ecological crisis has happened because we somehow weren‘t fast and successful enough in employing technological and scientific tools? I consider this a good example of the partial, temporary, negatively “speculative” thought model.

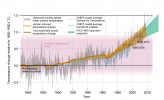

Techno-optimistic, instrumental thinking is dangerous in its impacts on the environment, as well as on ourselves. It replaces one threat with another, perhaps less visible one. It assumes we can solve the ecological crisis with cleverness, without us having to curb our consumption: for example, that we will send our garbage and pollution into space, or that we will solve the warming of the oceans by pouring iron sulphate into them, or that we just power our cars with electricity instead of fossil fuels. This approach has always most likely been predatory, shortminded and selfish in principle. But today we have unfortunately scaled it up: it’s no longer about the collapse of individual empires, cultures, tribes or communities. The non-manageable and anthropogenic processes seem to be so complex and mutually interconnected that they impact terrestrial, planetary phenomena. Is it possible that maybe there’s no longer a way back? With the help of mathematical models and artificial intelligence, we are fortunately, or unfortunately, able to even compute that we - as an organic species might be on the verge of extinction, taking a number of other species along with us. Like an unsuccessful biological experiment.

But back to numbers and data: apart from what is easily or, on the other hand, difficult to measure and calculate — like for example the temperature of air and water in the oceans, trees in a forest, the number of butterflies on the meadows, the titmice on the bird feeder, the weight of CO2, the tons of sand needed to make concrete artificial islands, square kilometers of natural gas, barrels of oil, kilometers of highway, the number of cars on the ground and of planes in the air — there are still (I believe) certain phenomena and volumes which do not subscribe to this accounting and statistical approach, this obsessive and responsibly irresponsible drive to enumeration … You may be able to add, subtract, divide, and multiply, but try to measure and weigh the mists in the valley, a dew drop lingering on a blade of glass, try to derive the rays of the setting sun falling on a snowy slope, try to multiply the speed of the dispersing molecules in a fragrance of blooming lilac, the decimeters of emotions, kilograms of poetry, decibels of bird song, decagrams of cloud, the kilowatt hours of water streaming past a scrum of rocks in white water…

I accepted Display gallery’s invitation as an opportunity to attempt to create the atmosphere of an insistent melancholy. Something like a no-nonsense form of environmental grief. But it seems to me that as soon as you turn to moralizing, to pathos — which I know I am usually running the risk of — you become laughable. A solution can be a lighter, perhaps slightly ironic, sarcastic mask or a saturnalian tone, a communal melancholy.

I was wondering what can still be considered essential for me today — and hopefully for the viewer as well (apart from food, drink, health, sleep and God) — and I found that these are heavenly phenomena: clouds, mists, clouds in nadir and their messengers — birds. With the arrival of Covid-19, the skies have cleared, as if the planet was for a spell liberated from our airplanes and their incessant noise. This decreased industrial production, as well as pollution, greenhouse gases and other missions and emissions. It was as if the birds returned along with the soft, voluptuous, colorful and flowing clouds. In some ways, the sky is still ungraspable for the human: it is distant, sublime, sometimes dramatic, terrifying. Still, albeit the ancient human dream of dominating the sky has almost come to pass in the last century.

To count and weigh clouds is possible, but I think it brings little satisfaction. It is much better to simply watch them. And the skies are easiest to observe when you lie down, look up, and don’t even focus your eyes. You look impartially, “speculatively”… You don’t have to think, your small, terrestrial thoughts and scale are exposed to the staggering, infinite grandiosity of the space above you… a 24/7, color, 180° program on all channels, with both day and night settings: so many colors and shapes! We watched the skies like this for hundreds of thousands of years, until someone found out that going into a cave or a room or a bunker has its own set of advantages.

And the counterweight for the installation to this heavenly and transcendental element consists of the stones on the ground. Or in the ground, which is still surprisingly determined to carry us: according to the alchemical principle, air is a cold element — everything which floats has no weight or firm shape. The changing fractal forms so far in the distance. Underneath our feet the endless enumeration of hard, oval, silent, patient, slow, archaic things. Stones are most likely the oldest terrestrials. They were born of fire and their shapes were made round by water. That is why we ought to revere them. We ought to similarly respect clouds as well, although geologically speaking the clouds and atmosphere are very young. I recently heard that during the epoch when life was forming on this planet, the skies were most likely orange, much like on Mars. So, we have a counterpoint between the sky and clouds on video, and stones on the ground. I worked with graphite on the surfaces of these stones shaped by the river current, and they gradually acquired the look of “as if” meteorites. These are rocks which have fallen to the earth from somewhere in the sky, from distant, other worlds. They may have been parts of other planets, asteroids, star stones which brought life to Earth? Towards the end of the exhibition, I will gradually return them to certain locations, landfills in and around Prague.

VB: You’re largely speaking about the exhibition’s first part: Of Heavens and Cornerstones. The whole exhibition however has three chapters. What will the other two be about, i.e. Soul Census and What’s Missing?

MV: Soul Census, the exhibition’s currently ongoing second part, is largely about the transmutation of air into pneumatic objects — mostly tiretubes and tires — and about the obsession with mobility in general, and about the automotive industry as a curse of the Anthropocene. And the last part will be paleonaturalist — it’s about evolution, extinction, survival, adaptation. We consider the dinosaur-lizards as a closed chapter, as a dead evolutionary appendix of life’s tale on this planet. But lizards have not disappeared at all! Some of them merely learned to adapt. The smaller and perhaps smarter ones experienced transmutation, a metamorphosis into birds. The great, cumbersome leviathans — stegosaurus, tyrannosaurus, ichthyosaurus, and who knows what other sauri — they were not able to handle the changing conditions after the fall of the meteorite. They were too cumbersome, too specialized, they were maybe unable to cooperate amongst themselves? Some achieved monstrous proportions and their energy consumption and metabolism assumed a huge intake of energy. This is a rather unscientific thought, but I imagine that some lizards, especially those who wanted and were able to fly, moved in that terrible winter and wasteland, and took refuge somewhere. Maybe Australia? It took them millions of years, but they finally adapted to a harsher climate, different conditions, different nutrition. And if you look around, they are living with us until today. And the cassowary is one of those witnesses of the tranformation. It maintained the aprearance of its ancient Jurassic ancestors. But the moral of the story for us seems obvious… Italo Calvino dedicates a short story in his Cosmicomics to this very issue.

Recently, my attention has been piqued by the term “disnovation.” It’s not really similar to the method of inverse technology, the practical philosophy of John Zerzan, the Dark Mountain collective’s agenda, nor Ted Kaczynski’s desperate protest, but it certainly turns the compass needle unambiguously towards setting course for a progressive future. Although it might perhaps be only metaphorical and within the context of an artistic concept… Nicolas Maigret’s and Maria Roszkowska’s disnovation.org, or the duo of Jim Haines and Joyce Hinterding are some among many others who attempt to deconstruct the myth of innocent technological progress as a certain ticket to the Disneyland of humanity’s Golden Age. They are wondering what path might lead us out of this mess. Perhaps we will indeed be able to retain something beneficial from that silo of humanity’s otherwise comic presence, but it most likely won’t be at all easy, pleasant or entertaining.

VB: Much like in one of the previous projects of the Center for Metamedia, Census loosely returns to the figure of Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680), the man who experimented with natural processes and often stipulated fantastical theories on his findings, in which spirituality and the dogma of European Modernity encountered geological and natural processes. In this regard, Kircher was in a sense a speculative thinker, and I am wondering just how much we can learn from his baroque works regarding the possible pitfalls of interdisciplinary thinking. Kircher’s example forces us to ask where lies the threshold between useful speculation and the formation of diverse, but ultimately pseudoscientific assumptions…

MV: It was rather Zbyněk Baladrán who mentioned Kircher in the exhibition’s accompanying curatorial text. I didn’t originally have him in mind when I was developing this exhibition, as I was rather focusing on Kircher during in the early 1990s. I am originally not a historian of science nor religion, but merely art, and so my historical knowledge of the Baroque era are rather superficial. René Descartes considered Kircher a charlatan, as a person with a perverted imagination. Descarte’s victorious — meaning the “rational,” mechanical, numerical — model of the world as a clockwork, including its benefits (such as the separation of church and state, science from religion, physics from metaphysics, science from pseudoscience), has for centuries enjoyed a dominant position. However: Cartesian conceptions of the world harbor an arrogant assumption that the only being endowed with a soul and with thought is the Human. According to Descartes, animals cannot think; they are merely moving mechanical machines. They lack emotion and so don’t feel any pain. The polymath Kircher did not consider the world as a ticking clockwork mechanism, made by God for the benefit of man; for him it was rather a strange theater full of astounding things, miracles and mysteries.

Kircher founded the first true Museum in his Jesuit college, which apparently included a large collection of exotic items and artefacts from all over the known world — today this would be enough to accuse him for his colonial bad manners. Kircher’s agile imagination and curiosity led to the construction of the strangest physical and pataphysical apparatuses / inventions — a sunflower clock powered and guided by the rays of the sun, speaking sculptures, installations made for eavesdropping, an organ played by water, a magnetic statue of Christ walking across the water surface towards St. Peter, machines for vomiting, and many others, besides his best-known invention, the Magic Lantern. He discovered, described and published encyclopedic compendia about the system of ocean currents, vulcanism and the subterranean world, magnetism, optics, acoustics, fossils, China … He did not manage to decode the famous Voynich manuscript, but he at least falsely thought to have deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphs. I think he was a bit of a dreamer, a poet, adventurer and empiricist: in 1638, during his trip through Italy, Vesuvius was just erupting and Kircher apparently had himself lowered into the crater so that could study the gate to the mysterious, plutonian netherworld with his own eyes. It matters little that the way he described his subjects applied only to his own speculative ideas and fantasies.

I was enchanted by just how masterful he was at combining systematic taxonomies and scientific erudition with a boundless poetic imagination. For example, when he “counted” the reasons for the fall of the Tower of Babel which was, according to ancient builders, supposed to reach the heavens — or at least the first lunar sphere. Kircher's conclusion was, that this was because the builders didn’t have enough material to build the tower. And secondly, it was because such a heavy building would "tip over the planet Earth" due to its mass. The Tower would finally plunge the world into a planetary environmental catastrophe. Physically speaking, such reasoning is bollocks, but metaphorically Kircher’s deductions were rather prophetic: he transposed a Biblical story on humanity into a "scientific" hypothesis which speaks about the erection of a monument to self-deification. Humanity wanted (long before the concept of a space elevator) to technically “reach” the heavens and colonize space. People thus precipitated ecological breakdown, a dislocation of the fragile balance of the cosmos, and finally their own confusion: of mutual understanding and languages. Since the time of the fall of the Tower of Babel, we’ve had trouble communicating, and it would be the case even if we would completely mastered a universal language of numbers — we can’t seem to agree on anything. And perhaps that’s how it will always be?

The interview was conducted by Vít Bohal

Miloš Vojtěchovský does not have a personal website, so his biography is uncertain and fickle, changing in space and time.