Message! Submit a message! Bring a message! Carry a message through the tumult! Not to look back once, to run across an immensely sharp summit, carry a message, bring it, for god’s sake, on time, and still undistorted, to run ever faster, bring it fresh, bring it and collapse on the ground, that is all.

—Ivan Diviš, Teorie spolehlivosti

Truth is the invention of a Liar

—Heinz Von Foerster

(Machine translated)

This essay presents — albeit more as a sketch — one of the topics I consider important when considering some European cultural activities of the 1990s. It is more a contextual and associative genre than a documentary. It touches on a number of topics and fields, such as technology, semantics, social relations, infection, immunity, cultural stereotypes and communication networks. It is a far from sentimental reappraisal of long-concluded stories — today largely forgotten — or of mere incidents taken from archives and dusted off (for example, as part of this year’s Transmediale in Berlin).1

I would like to thank those who have had the patience to read this work-in-progress, and have offered critical points and inspirational information: Dušan Barok, Martin Zet, Ondřej Vavrečka, Radka Schmelzová, and others.* --- I admit to a certain attempt at revision, as the established interpretation and reflection of the “small history” of the (Czecho-slovakian) refurbishment of state-controlled surveillance capitalism towards market capitalism often seems unsatisfactory to me: the transition from a “closed” to an “open” society2, the shift from shared poverty and a state of need towards “surplus” and waste, from “de-nationalization” towards privatization3; these are often missing the proper context. Maybe that is because this decade is rarely analyzed more deeply or impartially.4 The question is: To what degree can these rather marginal, fringe, artistic and “pop-cultural” initiatives, labeled as “independent” or “non-commercial” truly be called “independent” or indeed “autonomous”?5 What, from today’s perspective, does the term “autonomous” mean?

The various initiatives, the cultural centers, media labs, “anti-institutional” and non-governmental projects, artistic collectives (which were a thorn in the side of the neo-liberal wing of the then-contemporary economic forces), did they really spring up and close down of their own free will, by their own “decision”? Or was there also the interplay of circumstances? To what degree were the communities and collectives which served as intersections of, often opposing, economic and political forces and motives premeditated and constructed? The seismic upheavals in the fall and winter of 1989 resonated across Europe in mutually connected, vertically and horizontally strengthening and fading signals. Some spread from east to west, some went the other way; some from north to south, from underground centers of dissent to official structures, sometimes vice versa. At the same time, a discussion raged on the geopolitical and ideological contours of how to define the new situation of “central” or “eastern” Europe. Are the Baltic states in the same (cultural) sphere as regions like Romania or Albania? What are the connections and what values are shared among Austria, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, considering that the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy had happened some 70 years ago? Is it even possible, after 30 years, to write a report on the artistic collectives and cultural networks which usually did not survive this decade of transformation? Can one find some common features which would point to the strategies and motivations which might differ from those "parallel networks" where people used to meet, and discuss about environment, humanitarian aid, rock music, religion, tramping, or other practices? 6

### Patchworks, Networks and Globalization

Patchwork, or patching is “a traditional hand-crafting technique which usually consists in the mechanical linking of smaller, variously colored pieces of cloth into a larger whole, so that geometrical patterns are created.” Patching is a technique similar to knitting and sewing, and people most likely started practicing it 40,000 years ago. It is in that time frame that we find archeological remains of plant fibers which were used to sew together pieces of animal skin or cloth. The invention of the needle and thread is predicated on the specific anatomy of the hand, its fine motor skills, as well as cognitive abilities such as imagination, causal thinking, combining formerly separate parts into a new whole. The technology of montage, connection, stitching, knitting, weaving, or crocheting can be found in almost all traditional agricultural societies. Apart from cooking, baking, fermentation and other forms of food processing, tinkering, metallurgy and agriculture, patching was in place at the dawn of modern industrial society.7 The term “networking” is usually a term used in management. It mostly denotes the methods and know-how necessary for founding and developing companies, meaning it has to do with commercial tactics and marketing. It uses the theory and practice of the sociological and economic sciences and we often see it employed as a strategic tool in team building or knowledge management. More generally, networking touches on interpersonal relationships and communication, social, psychological, as well as cultural and economic structures, formations and strategies. Social networking is increasingly part of information and communication technologies and, with the advent of the internet and globalization, the level of “networking” is at a point where “inhuman” entities, such as bots or algorithms are becoming integral to it. They are also most probably becoming ever more dominant. In tandem with militarized media, the “autonomous,” self-regulating technologies and markets are inconspicuously pushing civic society to the sidelines, _“paralyzing our ability to think constructively, to make meaningful connections and to act with intent.

As if civilization itself reached the threshold of extinction, as if we lacked the collective will and coordination necessary to solve fundamental life questions asking about the very survival of humanity,”_ writes media theorist Douglas Rushkoff in his Manifesto of 2019.8 Network theory was certainly a hot topic in the late 1980s and early 1990s, regardless of whether they were communication, social, or neural networks; commercial, control, or power networks, closed or discrete networks, chaotic or organized. In the post-war fractured world (which was however increasingly permeated and connected by a mesh of journalistic, energetic, informational and gradually electronic networks and communication systems) networks had ambiguous connotations from their beginning. Is it perhaps because we had become parts of mirroring, antagonistic systems: worlds which were closely connected and mutually dependent? It was due to the anxiety and the drive to achieve a fragile equilibrium of military capital and nuclear weapons. From the mid-20th century, ideas of a universalist re-connection of everything and everyone with everything and everyone else under the banner of one victorious economic system made a periodic return. It might be that the ascendant maxim of interconnection will not only lead to singularity and the end of history, but will also increase instability and open the possibility of collapse. It might at least pose a threat to personal rights, such as privacy and other features of a civil society. The nightmares of the future as prophesied in the 1950s by Ray Bradbury and Philip K. Dick have, with the 2013 testimony of Edward Snowden, become all too real. Thinking “the network” along with the research done on transformation has, in contemporary vocabulary, come to be preferred over terms such as structure, paradigm, or system. Even before the advent of Web 2.0 and the reign of the “anti-social network,” the network has shown itself to be latently ubiquitous, and not only in the sphere of contemporary art and globalized culture.9

### The theory of networks and agents and the theory of parasites

An example can be found in the popular (albeit criticized) conception of the so-called "Actor Network Theory" (ANT for short). This is a materially-semiotic theory developed by three sociologists — Bruno Latour, Michel Callon and John Law, which they formulated as part of their research at the Parisian Centre de Sociologie de l’Innovation. The authors adopted a generally methodological or epistemological frame for sociology, post-structuralism, general systems theory, texts of Michel Serres, Deleuze and Guattari (Assemblage theory) and other sources. ANT is a hybrid network constituted by all active nodes. It connects various artificial and natural elements — actors can be organic and cultural elements, as well as human, machine, institutional, animal, plant, food or resource-based. Each one of the actors/agents has an equal value for the whole. Communication or cooperation take place in relative stability, dynamic symbiosis, but only until the point when one of the actors disappears, dies off, or another actor appears. This brings tension and turbulence to the network which can lead to growth, debilitation, dissolution or collapse.

The reason can be, for example, the collapse of a communication (telephone) network, malfunction of a military, control, commercial or banking system, the imposition of an unknown infection, parasite, virus, or the integration of a new — for example communication — platform (like the advent of electronic networks and their impact on the transformation of communication and commercial systems in the latter half of the 1980s). McLuhan's ideas about the impact of emergent technologies (for example of communication networks) which determine the economic, social and cultural relations, patterns and strategies — including the functioning of art institutions, artists and artefacts — are still relevant today, 70 years after their initial formulation.10 If we apply the concept of ANT to the sphere of “unofficial’ culture, or “artistically autonomous” happenings which took place around the same time as the fundamental upheavals in the region of central and eastern Europe, we can find a number of correlations in the increasing coverage of satellite TV (an assemblage of hardware, economic, symbolic and value formations such as culture and propaganda), the largely available apparatuses of data storage (audio tapes, VHS, video recorders) and technologies of copying and distributing texts (xerox).11 On the other hand, there was the formula of the censorship/surveillance system. We can also find signs of the “mysterious” or dark network in the workings of the surveillance/police state, which exhibits a complementary connection between the visible and hidden/discrete formations and agents which (just like in the case of the television network which connects the signal and the broadcast and receiving technologies) permeated both the public and the private spheres.

According to Michel Serres, the biological metaphor of the parasite was one of the first modes of human communication and excommunication.12 The term “parasite” comes from the Greek _para sitos_ — “to sit next to,” and in Czech and other languages it has a similar, tripartite meaning: an animal which feeds on or from the body of another animal, a slothful person living off the spoils of others, and noise in the decoding of a signal. The parasite lives from the body of the host, either on the inside or outside, and is a burden on its host, but only to a degree, as its existence relies on the host’s survival. Parasitic life strategies allow for long-term co-existence, and often a feedback loop is formed, so that the parasite provides some type of reciprocal service, establishing exchange — symbiosis. Parasites live from the remnants of other parasites. According to Serres, culture, art and language show certain signs of parasitism. The parasite creates disequilibrium in the system network, bringing disorder, chaos, which in turn breeds a more complex form of order. The parasite becomes the initiator of something new, something which is at first regarded as alien, subversive or disruptive. Parasitic (or pirate) strategies are complicit with the art of discovering novelty: Ars Inventiendi which, for Serres, constitutes the very essence of philosophy and art.13 In 1967, two authors of the Fluxus movement, Robert Filliou and George Brecht — much like the Situationists, or later media activists of the 1990s — thought that the network is “eternal.” They adopted the practices of camouflage and the strategies of mass media, advertisement and commercial corporations, despite the fact that their aims were socially and politically very different. Geert Lovink, one of the activists and theorists of the early 1990s who started to articulate the essence and sense of autonomous, free media, has recently become much more skeptical towards networks. The threat of a global network, a single Web, is nowadays interpreted in a much more realistic and gloomy light.14

### WWW What was the situation of communication networks in the Czech Republic in the early 1990s?

The first attempts at connection took place in the fall months of 1991 at Charles University. The line led from Prague (through the Czech Technical University) to an internet node located in Linz. Our Republic was officially connected to the internet on February 2, 1992 at the Czech Technical University. In 1991, the company Econnect was founded for a number of ecological initiatives around the Zelený kruh. Apart from the academic network, Econnect was among the first providers of access to the net.

In 1991, Tim Berners-Lee, in collaboration with a team of colleagues, proposed a coding language for creating web sites (HTML, or Hypertext Markup Language) and defined the HTTP protocol for transmitting websites through the internet (Hypertext Transfer Protocol). Berners-Lee also became the creator of the NEXUS program which was used to edit and browse web sites. The original proposals for naming the web were “Mine of Information” or “Information Mesh,” but ultimately the “World Wide Web” won out, and its services were provided free of charge.

In April of 1993 — two years after launching the service — the Austrian curator Peter Weibel addressed the phenomenon of the web as the main topic of a festival of electronic culture: “Welcome to the Wired World”. In the introductory text, Weibel writes: _“The postmodern society is based on information. No more the dynamics of mechanical machines but the exchange of data in the network of information machines supports the social operating system. Every day billions of humans communicate billions of massages via a global network which is constituted of telephone, fax, picture phone, mobile telephone, GPS (Global Positioning System), public access terminals, radio, pagers, TV, ISDN data communication, cable nets, cable TV, mailbox, e-mail, global computer networks like Internet, etc. We don’t live anymore only in streets and houses, but also in cable channels and telegraph wires, in fax machines and global digital networks.”_ But the distribution of information in mass media can also become a component of control and a source of optimizing strategies of power. Data opens critical questions about the dogmas and myths of post-modern information society.15 I mentioned Latour’s Actor-Network Theory because it seems a fitting metaphor to frame the story of the birth, growth and dismantling of various NGOs, non-commercial, and other “independent” artistic initiatives in central Europe, most importantly between the years 1990 and 2000.

I will try to show this using the example of the Hermit Foundation and the Center for Metamedia Plasy. I depart from the assumption that it was not only the personal motivation of myself and other involved initiators, but also the social-economic circumstances of the times, and the conditions, impulses, available technologies, time, space and the possibility of crossing borders. That is the amalgam of conditions for all the “actors” which rather became witnesses to the expected and feared disappearance of a long-riven and unknown world. Other factors, such as the chaotic state of the planned economy, the hibernation of the surveillance structures and the absence of a state-level cultural politics also played their part. The moment of _mimesis_, or the intuitive ability to distinguish, interpret, appropriate, transplant, evaluate or “translate” the foreign cultural templates, strategies and conditions was also important.16 A slightly de-mythologizing approach can uncover determinative relationships among the art histories and cultures as they were found in the regions. They might also reflect the current discussions on colonialism, or “self-colonialism,” in art, including the art of central Europe.17

During the organization of the auditory, visual and textual archive of the Hermit Foundation and the Center for Metamedia Plasy — as the project was paradoxically called — I kept encountering the idea, whether the name itself might not be hiding a subversive kernel, possessing a “diabolical machine” ticking away towards its self-detonation. What role could the foolish idea of hermitage have played in the project’s gradual extinction? The concrete idea and offer were drafted in the winter of 1991 and the spring of 1992, at two geopolitically and culturally distant places: in the half-abandoned buildings of the central European former Baroque monastery of Plasy, and the 900-km distant shores of northern Europe, in Amsterdam.

The genealogy of the idea, which at that time was still sketchy, was much older but the uncertain, grim, nomadic, homeless zeitgeist of then-contemporary Europe, with its unexpected outcome of 1989, certainly played a part. Was it a concoction of romantic dreaming about art, community, friendship and collectivism mixed with a dose of reality?18 On the one hand, the situation in the diaspora, the anxiety from a possible nuclear conflict of the great powers, feelings of uprootedness and alienation, and on the other hand the unclear idea about what all can be done in derelict, abandoned Baroque buildings, “far from the madding crowd” and far from centers of the “art world.”

Looking back at the annals of case studies (which rarely exist), it might seem that most “autonomous” cultural projects share one feature: only a few were created in isolation, but were rather connected and maintained through personal, communicational and economic ties and links, providing each other with a network of nutrients. It is important that, together with technologies of communication and “excommunication”, the political-economic landscape has changed: from interviews with physical, stable networks such as magazines, books, and other publications, telephone wires, post services, vinyl distribution and magnetic tapes adapted to electronic, digital networks, Bulletin Board Systems and web sites.19

The authors of the provocative study _Fame as an Illusion of Creativity_ published in 2018 write that social intelligence and a richness of social relationships was more important for the success of select European and American innovators of the first two decades of the 20th century than – as might be expected — their immanent artistic quality or creativity.20 It is true that subjectively I considered the residence, meeting and communion of all those hundreds of guests who frequented Plasy over the span of almost 10 years more important than the festival, symposia, exhibitions and concerts themselves.

Self-indulgence certainly played a part in this, because he who invited all of them to the magical place of the Plasy monastery somehow became somehow important himself. But as time went by, I found myself thinking the heretic thought that if someone doesn’t come and replace me in the position of the person who makes the next year’s event happen, I will just drop and quit everything. And eventually, that is what, in a way, happened.

Mokum (Amsterdam)

(Mokum is still commonly used as a nickname in the Netherlands for the city of Amsterdam. The nickname was first considered to be an example of bargoens, a form of Dutch slang, but in the 20th century it lost its negative sound). At the beginning in 1991 there was an almost accidental meeting in Amsterdam, where visual artists, musicians and writers from Czechoslovakia started to came since the spring of 1990. I tried to maintain the OKO Gallery - an exhibition space in the old house we have been living then and where several artists from Czechoslovakia have exhibited since 1989. It is important to say that since the 1970s the former colonial and maritime center of Amsterdam - similar as Berlin, Marseille or Copenhagen - has lost its "national atmosphere" and became - at least culturally - a cosmopolitan place. "Alternative" and "experimental" currents played a role on the art scene, or were at least tolerated, sometimes even encouraged. The relatively favorable economic situation and the social and immigration policies of the Dutch government have attracted a number of artists from Western Europe, the USA, Australia, Asia and Africa. After 1989, and especially during 1992, young people from Yugoslavia, refugees from the civil war, and gradually refugees from the crumbling USSR, found asylum here.

Since the early 1980s, squatting / kraak movement has spread in the Netherlands. Several autonomous art centers have been set up in Amsterdam, temporarily settled in abandoned industrial buildings (both illegally and semi-legally). Autonomous communities were often associated with pirated radio (Radio 100, Radio ADM, Radio Patapoe), even pirate television (Rabotnik TV), theater stages and galleries. There were many artistic community centers in Western Europe in the late 1990s. In the Netherlands, for example, in Eindoven, Hetogenbosch, Rotterdam, Cologne (since 1993 the Moltkerei Werkstatt), the Schedhalle in Zurich, and many others.

Technology - correspondence - communication:

The discussion and negotiation about the production of symposia´s in the first years took place mainly personally, by telephone, fax and by postal correspondence. In the early 1990s, the Artbook "art directory" was available in libraries, listing the mailing addresses of artists, critics, galleries, museums and art agencies in most countries of Europe and USA. I remember that I sent the invitation to the first symposium Hermit to aprox. 50 addresses, which I found here and where I estimated that the event could attract the addressees. In 1993, I bought or actually received instead of honorarium an Apple laptop (honorarium for the Orbis Pictus Revised installation project for ZKM) and started using a modem and fax to contact people in foreign countries, later via email. Even artists in Western Europe in the early 1990s, as far as I can remember, did not own a personal computer. I invited them with letters because international telephone tariffs were financially unaffordable. Construction in process: The European political landscape of the 1980´s looked like two separate worlds. In fact, not only after 1989, but also before, it was - albeit sparsely - connected by many personal and professional links, which, after the fall of the Berlin Wall became quickly renewed and strengthened. I was challenged how to create a place or an event where Czechs, visitors from abroad would be interested to come. What about the fact, that it was a place which almost nobody knows about? An important model for me was the visit of the photographic exhibition 9x9 in Plasy, organized by Anna Fárová and Joska Skalník in the summer of 1981. Another event I was able to get a personally involved was the International bourse of small, Independent publishers from all Europe "Europe against the Current". It was set up by the anarchist publishing house and bookstore Fort van Sjako in September 1989.

A certain information penetrated into Prague about the international symposium which Ryszard Wasko with group of friends - visual artists and filmmakers from the Lodz organized. They invited fifty artists from Western Europe and the USA to the symposium "Construction in the Process": promising them an apartment, food and materials, if they would pay for their travel. To express the support for the independent Polish culture and scene in a country where martial law was threatened, many artists - even established ones - accepted the invitation. For Czechoslovak "independent" culture - not only for dissent - was in the 1980s Poland and Hungary the land of freedom and goal of many expeditions to visit festivals and theater performances (especially in Wrocław, Gdańsk, Warsaw and Budapest). I listed below at least some of the institutions and initiatives with which the Hermit Foundation and the CMP may have been, or have been directly linked to, or which have been for us a model of inspiration. Most of the links are already listed in the web archive. Here are mainly projects and community networks to which it was possible connect with, or to use their platform and experience, or - at best try to support them (CMP attempted to do it in the last three years of its existence, when funded by the grant Pro Helvetia Ost West). The Cistercian reform and the Magicians context: Topos of the monastery, where the symposia took place, was decisive for shaping of the concept and program of the Hermit Foundation and the Center for Metamedia.

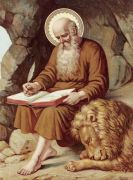

Therefore, I briefly researched the historical and cultural contexts of architecture, with a predominantly Baroque atmosphere. After coming to Bohemia, the Cistercian order established a network of convents from the middle of the 12th century, (gradually in Sedlec near Kutná Hora, Plasy, Mnichov Hradiště, Nepomuk, Klášter nad Dědinou, Mašťov and Osek). In the 13th century, the Cistercians built monasteries in Zlatá Koruna, Vyšší Brod, Zbraslav, Velehrad, Žďár nad Sázavou and Vizovice. Perhaps the largest and richest monastery in Bohemia was established in Plasy in the Baroque period. In 1785, as part of the reforms against the church, Joseph II. canceled the cloister. The brotherhood, with its spiritual and administrative center in France, from the beginning created an expanding network, which in a short period colonised almost the entire Christian Europe. It was established by splitting from the Benedictine center of Cluny - criticized by Cistercians for its excessive secularism and deviation from the original monastic ideals. Robert the Abbot of Molesme left with a group of brothers and in settled in 1098 near Dijon - (Cistercium today Cîteaux). Here they founded a new abbey. The community of monks practicing asceticism followed the "primordial" Christian ideals and order was in 1119 confirmed by Pope Calixtus. The most famous figure was Bernard the first abbot of the Clairvaux monastery his teachings and reform served to poverty and simplicity of monastic life. In accordance with the original order of St. In addition to piety, the Benedicts promoted physical labor, striving for economic self-sufficiency, ensured by a system of farmyards (grangias), where the lay brothers of the order worked.

Another inspiration was the catalog of the exhibition of the curator Jean-Huber Martin "Magiciens de la terre", which took place in 1989 at the Center Georges Pompidou in Paris. From a newspaper article, I learned about his activities in the Curios & Mirabilia project in the interiors of the Baroque Chateau d’Oiron near Nantés. The Magicians of the Earth exhibition is considered one of the first major projects to try to deconstruct colonial concepts of contemporary art. Based on the traditions of the Dada movement, Martin brought to contemporary art the works of hitherto completely unknown, anonymous artists from Africa and Asia. In Dada he found elements of "postmodernism" and an attempt to break the Western frameworks and stereotypes of art perception. The exhibitions at the Chateau d’Oiron were again a revocation of Baroque Wunderkamer, or "cabinets of curiosities", where art was confronted with objects of science and technology.

The Apollohuis network program was probably the strongest inspiration and the example to follow, although it is clear that comparing the conditions in which it operated with the improvised process in Plasy would be weird. However, the exhibition and concert spaces in the monastery were much more magnificent, which probably caused that one of the founders, Paul Panhuysen, was enchanted by the space and acoustics of the convent. The "Apollo's House" project in Eindhoven has been networking for more than 20 years in the form of promotion, creation and support of experimental music, sound and visual art, performance and, in part, the art of new media. The philanthropic sharing and exchange of information and resources was a basic idea for the Apollo network, as was solidarity with the art scene anywhere in the world. In 1980, the program was co-founded by the composers Remko Scha and the intermediate artist Paul Panhuysen on the premises of a former 19th-century cigar factory.

The project was partly funded by its own publishing activities, partly by grants from the Dutch Ministry of Culture and the Brabant Region. Between 1980 and 2001, Paul and Helén Panhuysen in Het Apollohuis, but also in Germany, Japan, the USA and elsewhere, held about 250 art exhibitions, 500 concerts and performances, 50 public lectures, symposia and initiated several festivals (ECHO: Pictures of Sound II. 1987, or FLEA Festival, 1997). They also organized a residency program, which was accommodation, a scholarship and access to a recording studio for guest artists who could prepare an exhibition, installation or publication there. Part of the archive was acquired by the Van Abbe Museum in Eindhoven, part of the archive was taken over and released on CD ZKM in Karlsruhe. The Apollohuise profile was also very international for Netherlands, It was one of the few places in Europe where experimenting artists from Asia, the USA, Canada and later also from Eastern Europe could get some support.

In 1992, Panhuysen helped me to contact several artists who attended the first year of the Hermit Symposium. At their own expense, they participated several times in symposia in Plasy. (In 2001 Paul and Heléne Panhuysen application was rejected the support because "their program was allegedly too international". Therefore, they finally decided to end the gallery's program and devoted themselves only to their own artistic activities.

Experimental Intermedia Foundation, founded in 1968 by Elaine Summers, has been presenting performances since 1973. Produced and curated by composer Phill Niblock, over 1000 concerts have been given at his loft, and he has opened his doors to hundreds of composers, giving them a place to explore the use of new ideas and technologies in their music. EIF continues to present at least 15 -20 concerts a year. The concert series are during March and December of each year. There are on occasion extra performance events that occur outside the usual concert series.Phill Niblock (1933), an American intermediate artist active in music, film, photography, video and new media is as capable a networker as Paul Panhuysen. Since 1965, he has been involved in film, music and intermedia performance, and curating and publishing music media. In 1985, he became director of the Experimental Intermedia Foundation, and in 1993 established a branch at his house in Ghent, Belgium. In Plasy, Niblock took part in the first Hermit festival, where they came with Paul Panhuysen.

Until his retirement, Phill taught at the University of New York and devoted his free time to obsessive travel and concerts. He was coming back to Plasy until the end of the 1990s, later joining the Ostrava Days of New Music festival. His work is often the result of collaboration with visual artists, dancers and other composers. In 2014, he received the John Cage Award from the Foundation for Contemporary Arts. He releases on labels XI, Moikai, Mode Records and Touch. He released four hours of two-DVD movies and music for Extreme. His large retrospective took place in Lausanne, Switzerland in 2013, organized by curator Mathieu Copeland and in 2015 in the House of the Lords of Kunštát prepared by Jozef Cseres.

http://experimentalintermedia.org

The Vasulkas: The meeting with Woody and Steina Vašulková in Amsterdam in 1989 motivated me to start preparing the Hermit Foundation concept. The Vasulkas were linked with the ethos of the counterculture of the 1960s, moving through the power lines of transnational cosmopolitan communities, networks and institutions, broadly connecting the liberal world of art (at least that;s how I interpreted it then). The Vašulkas had a presentation or screening in Steim (Studio for Improvised Electronic Music), where Steina later worked as an artistic director. I remember we discussed somewhere on the positions of mainstream and electronic art, which I knew very superficially. I was catched up by his parable that real Art should stay hidden, not try to negotiate too much with the public, because the seduction of success and popularity corrupt artists. We also talked about a network of shelters for creative people, inventors and artists, for whom such homes would be opened all over the world. The Vašulka founded in 1971 The Electronic Kitchen in New York, which was actually a model of a semi-dissident center, perhaps similar to the groups of artists in Central and Eastern Europe.

http://vasulka.org

Nettime, Next5min and Spectrum Mailing list Nettime, still operating today, was one of the first European communication electronic directories before the advent of social media. Founded in 1995 on the occasion of a meeting of artists and media activists at the Venice Biennale by Geert Lovink and Piet Schulz. In those years, Nettime played a key role in distributing information and creating an environment for critical discussion about the Internet, tactical media, and media strategies. In 2004 Nettime was awarded at the Ars Electronica festival. Over the years, there have been several international meetings of the Nettime network at events such as HackIt in Amsterdam, Chaos Computer Congress in Berlin, ISEA, the Ars Electronica festival, the MetaForum conference (95-96) in Budapest and the Nettime Conference - Beauty and the East, organized by the Ljudmila media lab in Ljubljana. The "The Hybrid Workspace" conference at Documenta X in Kassel in 1997 was closely linked to the Nettime community Next5min was an international festival and conference of tactical media in Amsterdam and Rotterdam. It took place between 1993 and 2003 on the premises of organizations such as De Balie, Paradiso, Waag society and V2. tacticalmediafiles.net Syndicate was a mailing list, an open platform for exchange and cooperation in media culture in Europe. Founded in January 1996 on the last day of the festival Next 5 Minutes 2 in Rotterdam, where the meeting was attended by 30 media artists and activists, journalists and curators from twelve Eastern and Western European countries. The list enjoyed the most active period until 1999, and existed until August 2001 (then linking 500 members from more than 30 European and a number of non-European countries).

The original idea was to establish an East-West network as well as an East-East network. In the meantime, however, the Syndicate had increasingly developed into an all-European forum for media culture and art. Over the last few years the division between East and West had been growing less important as people cooperated in ever-changing constellations, in ad-hoc as well as long-lasting partnerships.In September 2000 after a server crash, the list was moved to a new server hosted by OpenOffice.de in Berlin, and switched from Majordomo to Mailman administration software. The Czech cultural and art scene didn't get involved and interested in the European network concerning electronic culture and art or rather minimally. Maybe for similar reasons as in Poland. An exception was the Terminal Bar project, which had little contact with the Czech community and High-Tech exhibitions and festivals in Brno...

Pro Helvetia Foundation has been part of Swiss cultural policy since 1939. It was founded by the Federal Council "to defend the independent cultural identity of Switzerland" against Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. In 1940, it set up its first office premises in Hirschengraben in Zurich. In 1949, it became a public foundation with the mission of supporting Swiss culture and promoting it abroad. The mandate and organizational form were established in 1965, and international activities gradually predominated. In 1985, the Foundation opened an office at the Centre Culturel Suisse in Paris and Cairo. Pro Helvetia has established a number of branches in partnership with other institutions around the world. In Eastern Europe, Pro Helvetia Ost West was one of the most active foreign cultural institutions, and after 1989 it acquired the offices of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary.

As part of the Pro Helvetia Ost/West program, it financially supported a number of Swiss artists in the Czech Republic, and in 1997, the Plasy project, the Alfred ve dvoře theater, and the Center for Czech Photography.

Due to the political stabilization of the countries of Central Europe, the Prague branch closed in 2005. The director of the Prague branch was photographer Iren Stehli and the secretary was Jitka Altoe. prohelvetia.ch

Artist in Residence — Res Artist/Bethanien: In 1996, the director of the Res Artist organization Michael Haerdter came to Plasy. In 1974, he founded the Berlin organization Künstlerhaus Bethanien with a residency program and in 1993, the global network of artist residencies Res Artis. Plasy became a member of the residency network. I attended the Res Artist meeting in Berlin in 1999. The Czech born curator Miro Zahra came with Michael, who led, or perhaps founded, a residency program at Pluschow Castle in northeastern Germany. Other residency programs we collaborated with included Hotel Pupik Schrattenberg (Haimo Wallner), Californian Headlands in Sausalito, and others.

At the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic, they had not yet heard of such a thing as an artist residency, and calculating the accommodation allowance was truly an art. After the CMM activities in Plasy ended in 1999, the Soros Center for Contemporary Art leased a chateau in Čimelice to provide space for a residency program that ran for several years. An attempt at a residency center was created in Broumov (Petr Bergmann), MECCA in Terezín (Petr Larva), Cesta in Tábor, and perhaps elsewhere.

Ministery of Culture later initiated its own residency program in Český Krumlov, which still exists today.

Cooperation and maintaining contacts with cultural departments of the embassy were important and useful — for example, the Goethe Institute, the British Council, the Dutch Embassy, the Cultural Center of the US Embassy, which in the 1990s mostly supported the participation of their citizens in cultural events in Eastern Europe. The Soros Centers Network in Central and Eastern Europe. The Soros Center for Contemporary Art Prague began its activities in September 1992 in the Olšanka building, where in the first years it functioned as a special program of the Central European University (CEU). It was established as part of the patronage activities of George Soros, who since the 1970s had used capital obtained through stock market speculation to support activities in Eastern European countries. Under the influence of a group of people from the field of fine arts (for example, Meda Mládková), Soros expanded support aimed at the development of an open society and also at free artistic creativity. In 1985, The Soros Foundation Fine Arts Documentation Center was founded in Budapest at the Mücsarnok, and in 1992, the SCCA Network. Later renamed Soros Network Budapest and Center for Culture and Communication C3, led by Suzy Meszoly and Miklos Peternak respectively. The Hermit Foundation also had contacts with artists György Galántai and Julia Klaniczay, who led the Artpool documentation center in Budapest, founded in 1979. In the 1960s and 1970s, the most active networkers in the field of contemporary art in Central Europe were probably László Beke and Dora Maurer. In the 1970s, Beke organized a number of exhibitions and events that had a strong international context, similar to the activities of Jiří Valoch in Brno, for example. Black Market performance network: Contact: Tomáš Ruller, in Plasy there were Roi Vaara and Alastair MacLennan, and Zbygniew Warpechowski, who is not a member of the BM. The collective “jam sessions” of the Black Market movement were not conceived as “improvisation”, but as “the art of meeting”, and the art of “meeting”, in fact, as the art of “weaving a network”, where the participants act in mutual interaction, in the presence of the here and now — see Martin Buber’s motto: “The meeting does not take place in time and space, but time and space belong to the meeting…”.

Black Market International (BMI) is an international collective of performers, each of whom is dedicated to his own solo practice, who has been performing all over the world since 1985. The collective was founded under the name Market in Poznań by Boris Nieslony, Zygmunt Piotrowski, Tomáš Ruller and Jürgen Fritz in 1985. During their first European tour in 1986, they used the name Black Market. In 1990/91 they performed as Black Market International, but there are many versions of BMI,

blackmarketinternational.blogspot.com

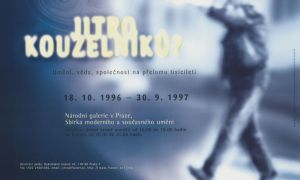

Terminal Bar: was the name of the Prague cultural center and company founded by Englishman Chris Stander. In the 1990s, an internet café was opened on Soukenická Street, where the company operated a bookstore, video library and offered clients internet access. The part of the company providing internet access and related services later became independent and was bought by the Norwegian company Telenor Nextel in 1998. The nationwide subsidiary Nextra Czech Republic was acquired by GTS in 2005. The Terminal Bar café went bankrupt in 2000. The founders of TB were Chris Stander, Dan Holman, Martin Neal, Brad Kirkpatrick, Morgan Sowden, Ron Barack, Charles Kane and Ken Ganfield. The main initiator was the Englishman Chris Stander (1965 - 2014). The designer of TB was Borek Šípek. Team TB collaborated with, for example, Prague Castle, the Ars Electronica festival, NG at the exhibition Jitro kouzelníků, and in 1998 at the Limbo I festival in Plasy. From the TB website archive: “Terminal Bar organizes lectures, expert meetings, festivals, conferences, art and technical exhibitions, and practical workshops for the public. In the interest of expanding cultural exchange, TB gathers various opinions from the Czech Republic, which is known for its magical history. The Czech Republic gave birth to and was home to many works of art, music, science, linguistics, and politics.

archive.org

CESTA International Cultural Center: Founded in 1993 by musicians Chris Rankin and Hilary Binder (Sabot) in an old mill in the center of Tábor. Chris Rankin attended the Hermit symposium that year (or in 1994). The goal of the cultural center, which was later published on its website, was to “improve cultural understanding and tolerance through art.” From 1993 to 2012, CESTA organized regular international art festivals, local community projects, creative workshops, and group stays associated with cultural activism for “artists of all genres, expressions, and backgrounds.” Their vision of developing cultural understanding was based on the assumption that traditional forms of artistic dialogue were limiting, and Cesta, with its open environment, sought to overcome such limitations and seek alternatives in a broader context. The Czech Republic offered a suitable framework from both an ideological and economic perspective. In a figurative sense, CESTA was a “laboratory where cultural work is connected with community projects” … “We do not think that CESTA is so exceptional that our activities are incomprehensible to those around us. We want to be one project among many, a project containing both the known and the unknown. Art is not limited to abstraction, ethereality, but contains socio-political aspects. Such cultural practice applies to everything we do, from cultural events to how interiors are arranged” (taken and adapted from the CESTA website).

cesta.cz

Transart Communication: “Studio erté Roco Juhasz” was founded in 1987 in Nové Zámky by József R. Juhász, Ilona Németh, Ottó Mészáros and Attila Simon. They closed the program in 2007 and the studio focused mainly on organizing festivals of alternative, experimental and multimedia art, performance, exhibition, publishing and educational activities. The festivals were part of the socio-political context of Central Europe in the 1980s and 1990s. The history of the group is captured in the book Transart Communication, Performance & Multimedia Art Studio erté 1987-2007 (Kalligram, 2008) in texts by Gábor Hushegyi and Zsolt Sőrés with extensive image documentation. József R. Juhász became a member of a global network of performers and artists from all over the world came to Nové Zámky.

studio-erte.sk

Mamapapa: was an independent civic association that was dedicated to consultations, courses, workshops, performances and projects in the field of alternative groups and individuals. It was established in 1997 as a result of the activities of the Dutch organization MAPA (since 1975 in Amsterdam). Mamapapa participated in events and projects of KALD DAMU, Four Days in Motion, Moving Academy for Performing Arts. It implemented projects in industrial buildings (Bubenská čistička, factory halls, warehouses, garages), in church buildings, in the open air, falconry houses, pubs (so-called site specific). Mamapapa's projects include: Zrod, Strom, Slunovrata, etc. (Mnichovo Hradiště 1997), Ritual of Place (Plasy 1998), Griftheater workshop in the Bubeneč wastewater treatment plant (1998), creative workshop with public explication of the performance 3W/window, water, wind (1998), LightLab as part of the Prague Quadrennial (1999), Eastern Harvest (Černý důl in the Krkonoše Mountains 1999), Demolice symposium (ČKD Prague 1999), Artes(t)CO (Máj-Tesco department store, Prague 2000), Midsummer Night's Night (Jičín 2000), Grain and Housing (Vojnarka Trstěnice estate, 2000), Body as a Boiler (Fišlovka boiler house ČKD Karlín, Prague 2000). Industrial Safari (Kladno 2005), Forest of Springs (Písek, 2017), Recykles — the path of wood (Prague, 2018), The Year of the Forester (Prague 2019).

Pantograph: was the name of the platform for which a pilot seminar was initiated by Miloš Vojtěchovský, Jo Williams from the Plasy Metamedia Center and Jennifer de Felice from the Center for Contemporary Art in Prague (formerly the Soros Center for Contemporary Art in Prague). The platform aimed to mediate and develop methods of cooperation, discussion and strengthening the emerging network of “interregional”, mainly local cultural and artistic projects in several countries of the former “Eastern Bloc”. These were to be more tightly interconnected in terms of communication, and thus to improve sustainability. The platform focused mainly on activities and areas that sought to create overlaps between art, culture and social and political issues. In 1994, a similar international seminar was held in Plasy, prepared by the Austrian art collective Die Fabrikant. 30 In 2000, we participated in the CAFE9.net project, organized by FCCA in Prague.

Divus: With the Divus publishing house, we prepared and in 1999 co-published the last CMM catalogue, documenting the Po-hádky exhibition and symposium. We met Ivan Mečl, who was one of the important Czech networkers, during the 1990s, mainly through Martin Zet. Ivan Mečl has been the spiritus agens of the Divus magazine since 1992, later the publisher of the Umělec magazine and the founder of the Prager Kabarret and Nová Perla projects. His approach was and is more from the realm of the artistic and adventurous than strictly business world. While most of the cultural-social-artistic activists who rose up in the early 1990s either gave up (Petr Bergmann in Dejvice and Broumov, Chris and Hillary in Cesta in Tábor, mamapapa anywhere, Krištof Kintera's Unit as well), or switched to another, business line. Mečl's ability to survive even the most difficult moments has led Divus through the vicissitudes of various hiding places in Prague, Vrané nad Vltavou, and finally to its own building in Kyjov near Krásná Lípa. Mečl is now building a winter garden from the production hall of a former thread factory, which he is renovating into an art center with a gallery, library, etc., and is even trying to acquire an adjacent pond. Nová Perla at the "end of the world" in Šluknovský výběžek conceptually resembles the vision of the planned Metamedia Center in Plasy. Only it is even further away from the centers and perhaps even autonomous. Mečl borrowed the name Nová Perla, which is a bit happier than Hermit or Metamedia, from Alfred Kubin, a native of Litoměřice and author of the book Země snivců. In Kubin's fairy tale, the city of Perla is described as "a place of unlimited possibilities for all dreamers," that is, for those who still dare to dream about something. divus.cc

Sam83 Gallery

Oddly enough, in Česká Bříza, near Plasy, the Sam83 Gallery was opened in 2006 as a subproject “Vision for a new culture and its place” as a background and space for a free field of thought. The initiator of the project, Sráč Sam, has been striving to create a “place of natural meeting” since 1993. In 2010, Sam83 Gallery and culture83 began residential stays and the publication of exhibition catalogues and the cultural quarterly PIŽMO. Technical, IT and media support for the gallery is provided by InterLab83. The gallery is self-financed, does not receive subsidies or grants, and its management is subject to the principles of eco-social economy (consideration of the origin of financial resources, minimization of consumption, justifiable investments). So an ideal constellation. The CMM in Plasy disappeared in the autumn of 1999, but after 6 years, 15 kilometers closer to Pilsen, another initiative was created in a similar spirit and with a more realistic program.