“Just as in this corporeal world there is a light

by means of which whatever things continue to be preserved,

also in the archetype, that invisible

and super celestial world, there is a light from which,

as from an abundant source, all things proceed...

and of which this material light is, so to speak, but a symbol.“

Athanasius Kircher, Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae (1646), Roma

A fictional interview on the Baroque, the growth rings of trees and the Hermit symposiums

From the window of the evening bus, the main building of the former Cistercian monastery in Plasy looks like some shabby ghost. It appeared to be levitating, an effect created by the evening fog rising from the valley of the Střela River. Cars drive past and a flock of pigeons circles above; two break away from the rest and land on the cross on the dome of the Chapel of Saint Bernard. The cross is in the shape of the letter T and a metal snake hangs from it. With the autumn evening at his back, the Visitor approaches the door to the building. He presses down hard on the large handle and squeezes through into the cold resounding darkness inside, where he is welcomed by multiple echoes of a closed door. He walks down a somewhat musty hallway to an illuminated broad staircase, climbs to the landing on the mezzanine and peers curiously down over the stone balustrade: the outline of his head is reflected on the surface of the shallow pool of water and the high ceiling behind it. The water seemed to ripple almost imperceptibly. The irregular rhythm of falling drops of water sounds from the underground shafts from which the water flows into the pool. Through the window panes into the garth, the Visitor sees the torn and faded red sheet of some sort of tent. He continues up the well-trodden oak stairs to the first floor and notices through the windows the symmetrical quadrature of the massive building. In a rhomboid section of window, a shrieking kestrel flies across the sky. The Visitor has the impression that a figure flashed at the end of the cloister and unexpectedly disappeared from his field of vision. He therefore heads to the nearest corner and suddenly sees the figure of his Doppelganger walking towards him. Startled, the Visitor steps to the side and glances back over his shoulder. He spots himself in a different mirror. He freezes with uncertainty as five tolls of a bell ring out in the corridors outside. The bells ring out again in a different tone. Luckily, a small door opens in the wall in front of him, someone peaks out, and the Visitor enters a normal, heated room.

VISITOR: (takes a seat) Hello, I am that Visitor. We spoke on the phone. Please forgive me, I missed my bus, so I am a little late. What’s with the sensory disorientation in the hallways? (sipping the coffee he has been given and peering incredulously at the ceiling, on which sunbeams bouncing off a mirror immersed in a vessel of water on the table in front of them are also flickering).

CASTELLAN: That’s just Michal Bouzek’s mirror installation. He set a mirror in each corner of the cloister so that someone walking in any direction down the corridor sees in the mirror either himself or someone walking in another part of the cloister corridors, or even sees what is happening across the way. But what specifically are you interested in here?

VISITOR: If I understand correctly – and that’s why I actually came – there was some kind of symposium here in the summer. The participants apparently worked with various historical spaces of this Baroque Bohemian treasure. Isn’t that a bit barbaric? Aren't they damaging the entire monastery?

CASTELLAN: It depends what kind of people they are what we let them to do. Of course, you’re begging for mayhem if you give free rein to a historical building to contemporary artists who have no respect for the space. They’ll hang all kinds of pictures and carve statues that don't belong here. But we try to make everyone who comes to the symposium sit still for a while before they start doing anything, so they get on the right frequency, get used to the place and take a good look around. And that’s why the Hermit symposia last two months or even longer. If possible, these are also artists who have some experience with similar projects, so they don't succumb to megalomania so easily. But if they do, the scale of the monastery overwhelms them anyway. Because this place is strong: the monastery withstood the Hussite Wars and Metternich’s absolutist imperiousness; it survived as a bivouac for the Red Army and endured the socialists’ notion of heritage care. Sure, these all left wounds and scars, but no one managed to destroy the monastery completely.

VISITOR: Why was your event called Hermit? Isn’t it snobbish, a bit of New Age puffery? Outside the monastery I saw a snack bar serving beer and hot dogs. Trucks drive by right under your window, and I saw a poster advertising a concert by the fabled rock band Brutus in the meadow out back next weekend.

CASTELLAN: Hermit sounds pretty good. A hermit is someone like an ascetic, a loner far from the madding crowd – someone who withdraws into voluntary solitude to hide or rest. And monasteries are basically housing estates, boarding houses for ascetics. Living in the forest and caves during the winter was probably pretty harsh and not everyone was built for such asceticism. All the brothers at the monastery had their own cell where they could retire to be alone. At the same time, they lived in a community with fellow brothers. They prayed together, sang, worked in the fields, ate, met in the garth and in the cloister. The Cistercian Order, which established this monastery, formed as a reform branch of the ancient Benedictine Order. Saint Bernard of Clairvaux and a group of followers went into the desert wasteland to purify the Order and to renew the evangelical simplicity of the Church. Bernard was a dedicated mystic and iconoclast of the 12th century. Order rules prescribed an austere lifestyle and physical work for the brothers. Even the monastery furnishings had to be plain and minimalist, and originally there could be no statues, paintings or ornament. This naturally changed over time as the Order became wealthy and the Cistercians lived relatively prosperously, as is evidenced by the monumentality of our monastery, which included extensive forests and properties in various parts of the Czech lands. But austerity remained in the rules. The artists working for the Cistercians in the Baroque period had to adapt to the original canon, which forbade ostentatious luxury and ornamentation of artistic design. Monasteries were a place where everyone lived together: lay people, sculptors, painters, musicians, scribes, carpenters, librarians, coopers, poets, apothecaries, mathematicians, cooks, gardeners, cabinetmakers, etc. The later division of artistic and craft types of activity had not yet arrived. Put simply: Hermit can mean anything and almost anyone can become one, but they must live with a certain degree of modesty.

VISITOR: (shaking his head in disagreement) Do you really think something like this makes sense today? That culture could or should separate itself from show business, the market and bootleggers? Isn't it just another foolish utopia of some fake return? A romanticising image of a past that’s gone for good?

CASTELLAN: The idea of the hermit and our programme will have a certain pinch of utopia in it. After all, what would we do without utopias, ideals and myths? What the ‘Hermits’ are about, or could be about, is pointing to interconnectedness, moderation and normality, not a desire for some sectarian exclusivity, turning up one's nose at the mundane. The word hermit also has something in common with hermeticism and perhaps even with hermeneutics, i.e. with the interpretation of something through something else. And in fact, it can simply be the image of someone who, through (apparent) solitude, is looking for a connection with others, with their surroundings, with nature, with the environment. It is the image of someone who is thinking about how to reduce their needs to the bare essentials. Someone troubled by constant distractions and temptations, as we see in those old paintings of St. Anthony. Today, there are all kinds of gadgets around, technologies that sell people the promise of easier and faster communication, tools that make our reality more colourful and beautiful than the ‘real one’. In the meantime, we are talking to each other less and often more superficially. We also don’t have time for anything. But the hermit – that crafty hermit crab – makes his time. He has got time to do nothing. He can quietly listen, look out from his hermitage/shell. He can think and even dream about something else...

VISITOR: What does that have in common with art? Wasn’t the symposium something artistic?

CASTELLAN: In the last century, avant-garde art cherished the idea of breaking with tradition, from the past, and refused to be tied even to its own ancestors. It created the phantom of complete innovation, but the veneer of uniqueness is wearing thin after those hundred years. The concept of gallery art is based on the principle of separation from ‘ordinary’ life, from everything that happens outside on the street. There was a lack of context because the artist aspired to become the essence of what is not yet, of what is yet to come; art was the harbinger of a future paradise. And an ancient and shabby place, such as the recently abolished monastery and its surroundings, is the complete opposite of such an artificial paradise, that sterile space of the White Cube. Such a wrinkled and scratched Place can serve as the ‘musical score’ for a conversation with the ‘other’, with the ‘ancient’, with the unknown. For example, with those who mastered their craft so well and who knew how to do it. In the monastery, the contemporary is confronted with a similar type of legacy; they have to recognise it and accept it, understand it – or they have to give it up.

VISITOR: And what does that have to do with your everyday life?

CASTELLAN: The figure of the hermit can be a guide for someone trying to engage with space and sound, but in a ‘different’ way than usual. It is an opportunity for someone who feels uncomfortable in the mainstream. The former monastery in Plasy is neither a museum nor a gallery; it is neither a space for accommodation nor a sanatorium. Symposium participants come here and find themselves in an environment that confronts them. Here, they must rely on themselves, on their own ability to improvise, on how they manage to deal with the original idea, how to design it so that it works in the place where they set it. Foreigners can’t speak with the locals and must find a different way to communicate. Although they work on their own, they can always ask others for advice. The position of curator, a person who determines what and how, is missing here. It is somewhat similar to the profession of a craftsman, but it requires at the same time a lot of thinking and observation. Everyone should be standing behind what they are doing, whether it is an installation, a performance, a concert or a lecture. But every action also inadvertently becomes interference and is evaluated against everything that happened there before, once upon a time, and against what others are doing. It is not an elite school situation, or a ‘sheltered workshop’ of the type you’d usually find in a gallery. It’s hard to cheat in such a building; in the end everything comes out.

VISITOR: You organised the second Hermit this year. How do the two years differ from each other? Was the previous work also connected with the notion of ‘sound and space’?

CASTELLAN: Last year was truly a leap into the unknown. The idea to organise a symposium and ‘art residency’ was almost automatic. Jiří Kornatovský was born in Plasy and is therefore its initiator. As the monastery looked and sounded rather empty, we thought we could invite someone who works with acoustics, who has experience with site specific installations or who performs various musical experiments. In the end, about sixty sculptors, installation artists, performers, and musicians gathered here; they alternately stayed and worked at Plasy from approximately April to September, i.e. over the course of nearly five months. At the same time, we partially modified sections of the monastery complex; we cleared the granary, from which the local agricultural cooperative, who stored fertilisers and peas there, moved out last year; we partially repaired the fountain pool in the courtyard of the abbot’s residence; we cleared one roundel, where the exposition of the liberation by the Red Army was held. Towards the end of the festival several musicians such as Fred Frith, Pavel Fajt, Phill Niblock, Paul Panhuysen, Anna Homler, Jo Truman, Oldřich Janota, Luboš Fidler, Orloj snivců and others came. There were several theatre performances, mostly people who are off the grid: neither academic moder nor ‘umpa-pa’ kind of music. They usually walked around the monastery dazed on the first days. Everyone came at their own expense – there was no budget at all. We managed to secure funding for a catalogue only retrospectively.

VISITOR: Not too many people knew about your symposium last year; was the promotion poor?

CASTELLAN: There was neither money nor time for things like promotion. The best promotion is word of mouth from those who were here. Competition in mass media is severe and Hermit should never become a mass event anyways. Once attendance reaches around 200 people, the monastery loses its magical atmosphere. A certain sense of seclusion should be preserved and cultivated.

VISITOR: Back to this year’s Hermit. What was the concept? What exactly does that ‘GrowthRing’ mean?

CASTELLAN: This year, 1993, was declared as the International Year of the Baroque. The title ‘GrowthRing’ is related to the passing of time, with a re-turn and re-view of the past. It also refers to the resonance of a panel, to a tree, wood, i.e. it’s related to sound. Borges says somewhere that the Baroque is a style that deliberately exhausts (or tries to exhaust) its own possibilities, and that borders on self-caricature. In a certain sense, the Baroque is every ultimate, or, if you like, decaying stage of an artistic period, an aged style which then exposes and exhausts its own resources. Sometimes we imagine the Baroque as excessive curls, as obese little angels flying with fat women across the ceiling heavens. But Baroque art is far more complex: it had tension and a dynamic that is missing from the subsequent periods of Classicism and the Rococo. And doesn't our current crisis resemble the old one from which the Baroque vision emerged three centuries ago at the end of Mannerism? Similar feelings of doom, devastation and a gaping infernal abyss somewhere around the corner? A similar desire for illusiveness and virtuality, a fondness for carnality, delight in titillating sexuality and simulated emotions? But also the need to search and renew something transcendent, something sacred in our life. We were interested to see how participants would react to such a concept and such challenge.

VISITOR: Did you have in mind ‘an unconventional’ form of the Baroque?

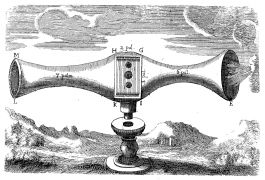

CASTELLAN: As the patrons of the GrowthRings, we chose two personalities from the Baroque period who are quite obscure yet still inspirational today: the priest Athanasius Kircher – the ‘Master of a Hundred Arts’, illusionist, collector, traveller, adventurer, inventor of light, optical and sound instruments and installations; and Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, a sculptor who during a few years alone in Bratislava created a cycle of (self) portraits with the most incredible grimaces Both seem very modern today.

VISITOR: What actually took place in Plasy this year? Who came and what was the focus?

CASTELLAN: We initially planned on at most fifty participants, but gradually this figure grew to around one hundred. That is already too many, and various problems and discrepancies were bound to arise. On the other hand, it’s the price you pay for creating an open event. We originally hoped that a lot of participants from distant countries would come. The dream was to have the most diverse opinions, means of expression, languages, colours and scents converge in Plasy. Unfortunately, it became clear that getting, say an Aborigine, musicians from Mali or Indonesia is no cakewalk and that a big production team and a sizeable budget would be necessary. Ours was paltry. In the end, it all came down to a few Japanese, one Chinese, a handful of Americans and an Australian. The pursuit of colour has been moved to the next Hermit. In terms of the types of art, there was a bit of everything: Slovakian folk music from Čadca, Jo Truman played the didgeridoo, Baroque lute with vocals – the duo Lewitová/Měřínský, harpsichord of Sarah Fraser, bass flute by Tibor Szemszö, wooden xylophones of Martin Groeneveld, electric guitar and flute Ann LaBerge and David Drama, trombonist James Fulkerson, Japanese eccentric Keiji Haino, drummer Pavel Fajt, Luboš Dalmador Fidler and Oldřich Janota; Orloj snivců, Richter Band, sound installations by Horst Rickels and Viktor Wentinck, Christof Schlägr, Bambuso Sonoro by Hans van Koolwijk, Irena and Vojtěch Havel on the viola da gamba and others. There was even a one-day concert in the Ball Games Hall at Prague Castle with many of the musicians who came to Plasy.

VISITOR: Music was apparently only part of the symposium programme? What about visual artists?

CASTELLAN: There shouldn't be set such a strict separation line here: after all, image, location and sound are very much related. For example, the installation Bees in the Bushes, which Ron Haselden placed in the granary cellar: in a completely dark space, he hung a system of colour LED lights that flashed irregular patterns at time intervals, reminiscent of the somewhat eidetic images you see when you press your fingers on your eyelids. The intensity of the light reacts to the volume of the bees’ buzzing, which Peter Cusack recorded in France. Descending into a deep, black, cold cellar where yellow lights flicker and invisible bees seem to fly around you in the dark: it's imaginary, but quite delicate. Because when you then climb up into the light in front of the granary, you will see a flowering linden tree that’s emanating the same hum, only much louder. You could also think that’s some kind of sound installation, but a closer look reveals that they were real bees. And you’ll see that they are flying to the hive they built in the hole beneath the Cistercian crest on the front of the granary. That this was an unexpected coincidence makes it even more beautiful, because neither Ron Haselden nor the bees probably knew about each other beforehand. Or Thomas Jacobs, who appeared here rather by chance and helped the others with their installations first: finally, he hung on wires from the ceiling of a room in the granary a large wooden pipe he had found lying outside in the yard of the prelate’s residence and probably belonged to the equipment of the nuclear shelter in the former cellars. He set a chair at both ends of the pipe, and when a person sat on it and put their ear to the opening, they suddenly heard an amplified ambient sound from the entire building, as if he were using a magnifying glass or a microphone.

VISITOR: But I also saw wooden sculptures, including a type of totem pole at the entrance to the monastery.

CASTELLAN: Several sculptors worked at the GrowthRings symposium – Sjoerd Buisman, Erik Wijntjes, Pavel Opočenský, Cees Gunsing, Peter Jacquemijn and others. The idea was for them to come to some sort of understanding and have some dialogue with the Baroque space, but most of them brought chainsaws, with which they played for most of their stay, somewhat polluting the surroundings with noise. We realised that that type of symposium wasn’t right for Plasy. But at the time there was nothing that could be done about it.

VISITOR: And what about performance and theatre?

CASTELLAN: Many performances were held in a wide range of monastery spaces over several weekends in June and July. Petr Nikl with the Mehedaha Theater held a night performance with candles and lamps in the chapel. There were performances by Věra Říčařová and František Vítek, probably the best Czech puppeteers, the Amsterdam underground groups Zyklus, and Hilary Vexil. Ryo Takahashi from Japan did a beautiful performance with candles, Marian Palla and Petr Kvíčala played ‘on nothing’ under the nick Florian, Tomáš Ruller set fire to the water surface of the water mirror in the main monastery building, symbolically penetrating into the underground, while acting rather alchemically. Cees Gunsing drew crowds to his pork celebration (vegetarians in attendance were not amused). At the end of the festival, Vladimír Kokolia put on something of an anti-performance and shut himself up for four days in a hand-made cell in the garth, where he drew and exercised without food or direct contact with his surroundings. This piece probably came closest to the spirit of the GrowthRings symposium. And there were also several lectures: the Dutch writer Anton Haakman as an expert on Father Kircher, performer Henri van Zanten lectured on F. X. Messerschmidt, and art historian Mojmír Horyna presented the work of J. B. Santini, who was the genius artist who designed the Baroque reconstruction of Plasy. It was more like shared information clarifying historical contexts and relationships to the present.

VISITOR: That’s good… but it’s another of your utopias… (accepts a glass of honey-coloured liquid from the Castellan). Will another Hermit be held at Plasy next year? (carefully sipping and inquisitively rolling the sweet liqueur on his tongue).

CASTELLAN: We hope so. Several colleagues and I founded Hermit as a foundation over the winter and obtained financial support from the Ministry of Culture for the project. The Prince Bernard Foundation gave us a grant for some technical equipment, so we can buy a fax machine and copier and get a phone line in the abbot’s residence, where we have a small office. The granary, unfortunately in sad condition at the moment, is to become the international Centre for Intermedial Art, conditioned, of course, on finding funding for its general overall reconstruction. It should include a documentation section – library, audio and video library, equipped workshops, an exhibition space and accommodation rooms for staff and guests. All of this is to enable artists and other professions from all over the world to meet here, say for a month, to meet and work on their projects in peace. A series of workshops and occasional exhibitions would continue during the summer. We already have contacts for similar art centres in Germany, France, England and the Netherlands. But I doubt that any of those have a building as beautiful as the granary at Plasy.

VISITOR: (suspiciously and inquisitively rolling the mysterious liquid over his tongue) But it’s probably going to take a long time. If it ever comes together at all! So, what are you planning for next year?

CASTELLAN: (refills the glass with the brown beverage) The next Hermit symposium will be more concentrated and shorter. We want to do the things that didn’t work out this year. We are collaborating with several organisations that support art outside Europe. With their help, we want to bring musicians, artists, dancers, etc., for example from New Guinea and Mongolia, to meet at the monastery, in the ‘centre of Europe’. In other words, we will invite someone from a culture that until recently was referred to in Europe as exotic or barbaric. We will bring them here to the Czech environment, which is often distrustful of anything different and ‘foreign’. The project strives for the ‘colourfulness’ I already mentioned. Since the local monastery was Catholic and therefore one of the nods of the Universal Church, it could serve as the perfect place to pursue ancient Comenius' idea of universal ecumenism.

VISITOR: (tilting his head back to finish the last drops of liqueur and looking at his wristwatch in surprise). So, one last question: what exactly am I drinking here?

CASTELLAN: (pulls out of the sideboard a dimly glowing bulbous bottle with a faded label showing a kind of pipe with a pair of fellows communicating through it) This is our ‘Monastery Secret’ – an herbal distillate made from the local curative mineral water and thyme and centaury from the sunlit slopes. It was part of an alchemy project conducted in the monastery underground. Not too bad for a first try and the fact that it’s ‘art’?

VISITOR: (gets up and accidentally knocks over a chair) Not bad at all. For a first try.

He walks a bit unsteadily to the door, opens it, shakes hands with the Castellan and leaves through the cloister to the left. He accidentally heads towards the spiral staircase up to the second floor, where a female voice is pronouncing the names of unknown angels. After looking into the passing ascending spiral perspective, the Visitor’s head starts to spin again.

Miloš Vojtěchovský, Plasy, Prague, Amsterdam, 1993

Text taken from the magazine Vokno no. 29/1994, pp. 28–31

Editing: S.M. Blumfeld aka Lubomír Drožď - Čaroděj OZ, 1993, and Miloš Vojtěchovský 2023

Translation David Gaul

(for the book Flashback, Hermit 1992 - 1999, published by MUO in 2023)

/1993/

Editing: Lubomír Drožď - Čaroděj OZ

Taken from the Vokno magazine: Vokno No. 29 / 1994,p. 28-31