The exhibition The Most Beautiful Catastrophe (2018, curated by Jakub Gawkowski) was held at Kronika gallery in the Silesian town of Bytom between December 3 – 14, 2018, just a short tram ride from Katowice’s International Congress Center where the UNFCCC’s 24th Conference of the Parties took place. The exhibition featured numerous works of Polish, Czech, Slovak and Hungarian artists, and set out to “problematize the very concept of nature” and “rethink the future of the planet and the relationship between humans and the environment." It is this preoccupation with “the future,” which will constitute the main thrust for the following essay through contextualizing some of the impacts which art may have in staking out a navigable modus operandi for future society.

How can a catastrophe be beautiful? How can the age of the sixth extinction be described as anything but horrific? One answer seems to be that it is a question of utility: the capacity for experiencing and communicating beauty constitute a pragmatics of communication. Following Kant and Lyotard, one may say that “communicability” is always “presupposed in any conceptual communication,” and that this communicability “always takes place immediately in the concept of the beautiful” (Lyotard 109). Beauty is thus posited as an immediate frame through which intersubjective and intracultural communication is made readily available. Without the opening up of space for aesthetic reflection, the dire reality of ecological collapse would remain an ephemeral, non-communicable potentiality. As such, beauty and art can provide a semiotic repertoire for addressing the “global weirding” (Friedman) of both the political and meteorological climate which the planet is currently undergoing.

A second reason for the validity of framing a “beautiful catastrophe” is that the category of the beautiful constitutes a potential horizon for restoration. For society to carry on in the whirling dust of a future planet without a concept predicated on the existence of "the beautiful" would be in the coming decades impossible for the human animal. The presence of the human integrally implies a capacity for experiencing beauty and, as such, the category not only provides a traditional frame of communication which allows the human to prepare for the difficulties which lie ahead, but also allows society to extrapolate our culture into its difficult future.

The Pragmatics of Beauty

Following the first line of thought, Lyotard sees beauty as a fit between nature and mind, or “imagination and understanding.” The sentiment of beauty is a packet of information always already prepackaged for the beholder through cultural conditioning, and as such plays an important role in the functional communication of a referent. The referent in the case of The Most Beautiful Catastrophe is the impending climate crisis, and the thesis would thus necessitate that ecological and social collapse must be made beautiful if the human animal is to reflect on it, and properly respond to the challenge of its survival. Beauty, in this case, does not serve as a form of escape predicated on a simulationist semiotic paradigm, but rather serves as a method for integration and for the reflection on the reality of social deceleration and possible catastrophe.

It is useful at this point to offer a mild reading of the aesthetic category of “the sublime.” Climate catastrophe is most certainly an almost epitomic example of a sublime event. In the work of the modern godfather of the sublime, Edmund Burke, the sublime is that feeling which mingles “terror” and “pleasure.” Lyotard later writes that “The aesthetics of the sublime [is] indeterminate: a pleasure mixed with pain, a pleasure which comes from pain” (Lyotard 98). This improbable marriage between the two is possible when “the terror-causing threat be suspended, kept at bay, held back. [...] This is still a privation, but a privation at one remove” (Lyotard 99). The unwinding chain of ever greater remoteness, which takes us away from the dredges and tailings and toxic streams which poison our lands and our bodies is suspended at ever greater remove: the excavation process which starts in the dark bowels of the Earth where we mine carbon matter seeded through the geological processes of millions of years continues in the coal-burning, peripheral places, and offers the general population only epiphenomena from which to glean the dispositions of climate change. The gallery spaces which then beautify and curate the issue even further remove the problem further from its material substrate, sublimating even further the primal terror of being faced with the demise of one’s way of life, and of the world-for-us as we have known it. The sublime is thus the feeling of “relief” we encounter when we realize that impending doom is still not present here with us, is still removed from our direct vicinity, is still happening to someone else, somewhere else. The margins are however collapsing ever quicker into the center, and the sublime image of climate catastrophe in many instances gives way to the fundamental terror which underpins it. The state of the anthropocene can thus be aesthetically conceived as an age of constant shifting in the horizon of sublimity. Lyotard (99) writes that “the sublime is kindled by the threat of nothing further happening,” meaning that the experience of the sublime has is always poised on the brink of the world-for-us and the world-without-us (Thacker).

In his now-classical essay “Deep Adaptation: A Map for Navigating Climate Tragedy,” Prof. Jem Bendell heralds the reality of “inevitable near-term social collapse.” His work summarizes the newest findings as “indicating inevitable collapse, probable catastrophe [and] possible extinction.” It is this realization of its own possible extinction which must be accepted as a possibility on the part of “the human” (here understood as a useful discursive construct), if only to properly grieve and work through its personal and social implications. Gazing at this “blind spot” of culture opens the door for the underlying subsonic murmur, the terror which underpins the sublime experience, narrowing the threshold of “remove” ever closer. Grief and mourning form an integral part of acknowledging the dire reality of our situation, and, on a pragmatic level, the sublime experience can facilitate just such a coping on a personal level, albeit remaining incommunicable at the interpersonal. Beauty in this sense communicates reality intraculturally, and for a catastrophe to be pragmatically analyzed and reflected on various social strata, it needs to be made invested (i.e. “dressed up”) and beautiful.

Towards Restoration

As a communicative tool which is tempered by aesthetic perception towards further “remove” of the sublime terror, the beautiful can, through its dogged insistence on the human scale and on the validity of its semiotic constructions, further work as a vehicle for navigating the difficulties which lie ahead. “The beautiful” is implicitly anthropocentric, but gloriously so, as it opens space for the necessary restoration, or “greening,” of the future world in both the literal and metaphorical sense.

It is helpful to contextualize Restoration within the tripartite typology which Prof. Bendell proposes as part of his Deep Adaptation project: the three “R”s are Resilience, Relinquishment, and Restoration. It is the last, Restoration, which is carried through by means of beauty – of the human and for the human. Beauty is an integral part of the cultivation of the world-for-us, with all its multi-faceted topologies, and can thus play an integral part in conceiving the post-anthropocene landscape. If culture, as a socio-economic as much as an aesthetic construct, is to survive, it must have a conception of beauty, if only to accommodate a process of gradual biological, material and psycho-spiritual restoration.

Through its close interconnection with the category of the beautiful, Restoration however becomes a problematic, two-pronged concept – in one sense, through a reflective gesture, it restores that which was in place beforehand, but on the other must also remain promethean and cunning in its relationship to the deep future. Restoring the beautiful must not fall prey to a nostalgia, or a being-in-the-world predicated on hauntology, but must, in Bendell’s words, consist in asking “what can we bring back to help us with the coming difficulties and tragedies?” Although investment into the beautiful is predicated on an unabashed presumption of the continuation of the human Dasein as such, it must extrapolate certain features of social praxis which will have the desired impact on the human experience. Its underlying strength rests in its relevance for crafting a biophilic future: the category of the beautiful is always inscribed as a coupling of the human with the world, and thus posits a firm stake in the well-being of the biosphere and of its human parasite. The extrapolation of beauty will thus constitute a skeuomorph which will allow the world-for-us to exist and persist, and which will mine the past for the best it has to offer, while understanding that history moves ahead.

The Beauty of Restoration: Kaszás and Lelonek

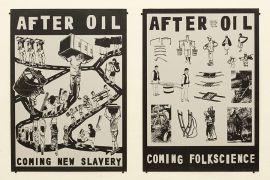

Some of the art works exhibited in Kronika thematize such temporality, excavating a space for beauty in the post-anthropocene. Three projects notably work with the implicit theme of reclaiming and restoring those modes of praxis which may prove to be useful, using the white cube gallery-form to present projects which syncretically tether the past to an inchoate future. These were the Sci-Fi Agit Prop Bulletin Board (2009-2018) prints of Tamás Kaszás, and two projects by Diana Lelonek, the Seaberry Slagheap(2018) and a showcase of her works from the project Center for Living Things(2016 – ongoing).

The prints of Kaszás formally hark back to Hungarian socialist propaganda, but are predominantly themed on the adoption of resilient technologies. They graphically excavate primal potentialities of the body and of human culture which Kaszás re-choreographs for the coming age of environmental and socio-political collapse. Kaszás series on the “Coming Folkscience,” as well as his envisioning of a society “After Oil,” communicates the skill sets of former modes of production, allowing the audience to think of a 21st century, bricolaged salvage patch. As such, Kaszás reworks the terror of societal collapse through extrapolating tried and tested modes of production into the future, depicting a “human community formed on the ashes of the old world” (exhibition catalogue). In this series he is “using easily accessible materials and simple techniques [both in content and form] that in the future – after the catastrophe – will again become a common method of communication.” His project thus combines methods of resilience with those of restoration, mining the past for skill sets which will become increasingly relevant in a post-sustainable future.

A similar idea is evident in Diana Lelonek’s Seaberry Slagheap project which uses the seaberry plant (Hippophae), a “superfood” rich in vitamin C and antioxidants, for developing a line of local food products. The seaberry is native to seaside, sandy soils, but also grows abundantly in the barren soil of restored, post-mining areas, and Lelonek’s project thus directly contributes to the restoration of former open-pit mines, re-engineering the landfills and revivifying them for the use of a post-coal society. The seaberry has a complex root system which retains water in the soil, and the plant thus in fact promotes the growth of other plants and prevents soil erosion wherever they are planted. Lelonek’s second project, the Center for Living Things aesthetically communicates a similar goal of restoration, presenting “the after-life of human-made objects that lost their original function and came into relation with other organisms or became their nutrient” (exhibition catalogue). These hybrid objects of living and non-living matter speak directly to the greening potential of the biosphere, and reclaim a stake for the living within an ever increasingly inhospitable world. They aesthetically point out the biopshere’s life processes of integral growth and adaptation, building upon the decomposed remains of the anthropocene. Lelonek’s project gives an inhuman perspective on Kaszás’ “community built upon the ashes of the old world,” and thus offers another reading of the potentialities for restoration and post-anthropocene repurposing.

These two artists directly express that the very condition of making art in our day and age has an underlying pragmatic level, and show that a positive vision of restorative greening plays an important role in both the social and the subjective spin on understanding collapse. It is spaces like Kronika gallery which nurture such a need for the continuing perseverance of the category of “the beautiful,” if only to allow for the accommodation of the two effects of communication and restoration. How difficult the coming decades will be remains up to the decisions of humanity and its protocols, but one thing is certain: the coming decline, which will inevitably transpire in certain parts of the globe, will always retain a latent potential for beauty, and as long as the human is there to perceive it, such a disposition will retain its pragmatic functionality.

Vít Bohal

The exhibition was realized with the kind support of the Visegrad Fund.

Citations

Bendell, Jem. “Deep Adaptation: A Map for Navigating Climate Tragedy.” IFLAS Occasional Paper 2. accessed 18.12.2018 https://www.lifeworth.com/deepadaptation.pdf.

Burke, Edmund. A Philosophical Inquiry into the Sublime and Beautiful (England: Penguin Books, 2004).

Friedman, Thomas L. “Global Weirding is Here.” NY Times. 17.2.2010. accessed 18.12.2018 https://www.nytimes.com/ 2010/02/17/opinion/17friedman.html.

Lyotard, Jean-François. The Inhuman (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988).

Thacker, Eugene. In the Dust of This Planet: Horror of Philosophy, Vol. 1 (UK: Zero Books, 2011).

The Most Beautiful Catastrophe (cur. Jakub Gawkowski), exhibition catalogue (2018).