Artist Tomáš Šenkyřík builds on his experience in the music scene, even though today he largely works in the gaps between disciplines. This is especially true for his field recordings of nature and landscapes, which he presents in the form of recordings, lectures, internet releases, and gallery installations.

Šenkyřík mostly records his material in the area around his hometown of Židlochovice and in South Bohemia, attempting to capture the acoustic identity of these places, as well as their transformations over time. In addition to his musical approach, he is also interested in the scientific and environmental aspects of the places, such as when he documents the fading choir of frogs which signal the destructive impact of drought, or the increase in song intensity of birds as means of compensating for rising levels of man-made noise. The artist then presents his recordings online, for example on Soundscape, a platform for similar research, and he also uses them in his lectures, workshops and other environmentally-focused events. These interests also go hand-in-hand with his position as deputy mayor of Židlochovice, where he similarly emphasizes ecological and environmental issues, such as the need to retain water in the landscape with the help of wetlands or other bodies of water.

When did you first become interested in working with field recordings?

Around the turn of the millennium, when I finished school and was returning from civil service, it was a very interesting time: You could buy the first minidisc recorders, and they were becoming increasingly affordable. You could also, for example, still find Roma musicians who remembered the second World War and, as an ethnomusicologist, I had the opportunity to go to these Roma communities and record relatively authentic Roma folklore. It was then that I realized that fieldwork was very close to my heart, and I realized to what degree the authenticity of the Roma musicians was key for the recording as a whole. I became obsessed with going out into the field and recording. After 2008, I started recording natural sounds and soundscapes, but did not really release anything. Only after 2015 did I start to regularly record and compare the various sounds, environments and so on.

Has your recording practice at all been influenced by your musical education?

I consider them related. When I am in nature, I listen to it as if I were listening to a musical structure. Sometimes I am so drawn in by it, that I experience it as a musical piece with leitmotifs. In his book Mýtus a skutečnost hudby (The Myth and Fact of Music), my former teacher Mr. Fukač writes that the beginnings of music are connected to the experience of soundscapes. The inhabitants tended towards imitation, and they thus transformed these structures and further styled them, and that’s how music was probably created. But the materiality of a sounding environment can be approached in various ways, and this is just one of them.

An ornithologist can focus on the voice of a single bird, while others might record an entire soundscape and interpret it, for example, from an environmental perspective. You furthermore add the musical perspective which you have described, and often consider your work as a kind of composition. In the past, you used to focus on natural sounds, but today you experience the environment within its broader context. Can you describe a bit more the way your relationship to field recordings developed in the past?

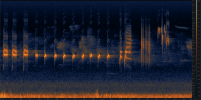

When I started regularly going out into nature to carefully listen, I realized that I preferred only to listen, rather than to actually record. We talked with Peter Cusack about how the best recordings seem to be those which were never recorded. And at that time, I used to experience anthrophony as wholly disruptive. It has to do with the seemingly healing properties of the pristine environment, for example the sound of a waking forest. At this particular, and very magical, moment, you hear sounds and smell fragrances, and I think this is something which all of us carry within us, archetypally so. Historically speaking, the sounds of engines have been with us for a very short time in comparison to sounding structures made by nature. I am deeply convinced that biophony and geophony are something which is part of our identity and being. And that is the reason why I once considered anthrophony disruptive. I did not try to suppress anthropogenic sounds in post-production so much as rather edit them out completely, and so I was creating for myself an acoustic world which might have been heard before the invention of airplanes, engines and sound pollution. I felt good in such a world and found it interesting to study how this infinite jukebox — the planet — sounded before the arrival of the human. You can also scientifically study the functioning of natural structures. When you put the recording into a spectrogram which graphically depicts sound, you see just how beautifully all the sounds are interconnected. Somewhere it’s the spotted woodpecker, with a blackbird singing a bit higher, and the frequencies above that are taken by the common chiffchaff. It’s like a musical score, this order in which the individual types of bird complement each other, never encroaching too much on each other’s niche of acoustic frequency. I find this immensely interesting.

But as I moved through the environment more, listening carefully all the while, I began to be fascinated also by the way this untouched infrastructure started to change due to the input of anthrophonic interventions which, for example, scramble a chorus of frogs, or make a bird start to sing a bit higher as a form of compensation. These are micro-utterances of changes in structure, and it is a great adventure to observe and study them. But I am again talking about other approaches — it is all very interdisciplinary. For example, an ornithologist can be interested in how a titmouse in the city is driven to start singing a half-tone higher in order to beat the noise of traffic simply to procreate. Or you can approach it from a musical, bio-acoustic, or eco-acoustic perspective.

My perception of human sound and biophony really changed when I was recording a toad in the local wetlands. Very soon a plane passed by, and created a new, low-frequency drone sound, advancing by quartertones, half-tones, changing the background. If I transposed this to a musical score, the cello would be the plane, the frog calls would be imitated by flutes and bassoons, and the common chiffchaff would be piccolo. When you create a spectrogram of an orchestra, you see how we transfer these structures — the sounding environment — into our own forms of artistic expression.

How did your relationship to the landscape and nature in general develop?

It was given by the fact that I grew up in Rusava near the Hostýn highlands, where I record to this day. I generally go to locations I know. Already as a child I remember being fascinated by the song of a blackbird, its melodies and creaking voice. I always used to look forward to the spring to when I would hear that, as it made me feel physically good. For example, I would go to tennis practice down an avenue lined with trees where one blackbird sang, and that motif to this day takes me back to the days of my childhood.

Were you inspired by music as well as acoustic ecology?

Certainly. In music it was mostly Leoš Janáček and Olivier Messiaen. Especially Janáček, who was in fact “sampling” with pencil and paper when he recorded Brno’s Zelný market and then transposed the people’s exclamations into his musical score. And then also the very first recordings of folklore and folk music recorded in their original environment; this was all very inspiring for me. And regarding field recording: in 2000, I prepared the CD Giľa Ďíla Giľora, which contains the oldest recordings of Olaš Roma, recorded in the 1950s by Roma scholar and friend Eva Davidová. She deposited the originals in the Phonogrammarchiv in Vienna. There I met one lady, Christianne Fennesz Juhasz with whom we were processing Davidová’s collections, as well as her husband, Christian Fennesz. He released some of his work under the label Touch, which drew my attention to the work of Chris Watson and Jana Winderen who focuses on acoustic ecology and records what is happening under the ocean surface. Encountering these artists was a bit of a milestone for me, and also an initial source of frustration, seeing the prices of the devices they were using. I read their websites and interviews, and each of their ideas greatly impacted me.

What role does technological experimentation play in your work?

I am not as skilled in using technology, as for example Michal Kindernay or Jonáš Gruska, and it would take me too long to learn. I prefer to work out in the field and save up for any piece of tech or recording device I might need. Although this can sometimes take quite a long time.

How do you present your recordings? You currently have an ongoing exhibition at Jihlava’s OGV.

There is currently a spatial sound installation entitled “Příběh Plačkova Lesa” (The Story of Plaček’s Woods) in Jihlava. I’ve been going to the place for seven years, and I wished to transfer its emotional contours, the magic of this space, as well as its acoustic identity. I think the spatial installation is ideal, as our perception is also spatial. As we sit here, you are listening to me, but you also notice that someone is walking behind you and that the floor creaked, or that a teacher is guiding a class of students just beyond the window and hear the subdued voices of the children, although you filter this out to a certain degree. And I similarly try to mediate Plaček’s woods. For example, the recording features a grand chorus of frogs slowly encroached on by the sound of a passing train which then gradually fades. The installation shows everything as it is. One lady who went to the exhibition told me that she had the feeling of standing within an acoustic sculpture, and this gives the greatest satisfaction for me — when the work evokes a sort of physical experience, and sound becomes some form of physical material. It is very important to experience this for yourself.

I am currently preparing another large installation for the Médium Gallery in Bratislava. It will again feature four channels. I have been going to record there since last December, and it is beautiful not only for its biophony, but also for its interaction with anthropophony.

You mentioned workshops, and you also release recordings…

These are all various channels which facilitate communication with the listener. When I am making a recording for the internet or recording for the Skupina label, it is something different than if I were preparing a sound installation. And a workshop with kids or adults is again something different, as I feature shorter recordings, and the verbal commentary accompanied by photographs of the place and so on become more important in such a setting. I don’t feel particularly able to determine birdsong, and that’s why I work with local ornithologists.

I don’t really do workshops now, due to Covid. But previously, I used to do them at festivals, for example in Jonáš Gruska’s LOM in Bratislava, and we had a few lectures with Skupina, that is Ján Solčáni and Filip Johánek. Filip occasionally also had me as guest for his lectures on interactive media at FSS in Brno.

You say your recordings are important to you, but what do they give your audience?

I will start with the children with whom I had the workshops. Interesting and fascinating things, and I don’t just mean in the visual sense but also in the sonic realm, begin to occur just outside our door. You don’t always have to go to Africa or somewhere, and the kids may realize that it only takes a trip to the garden or to the nearest hill, Výhoň, to experience a whole spectrum of extremely interesting things. All you have to do is open your eyes and ears. And when I talked to the kids about ecological issues, I saw that sound had a tremendous emotional impact on this young generation. It greatly helps the child to make the proper connections when the recording is accompanied by spoken commentary. I think it is very important to transmit the things in a way which connects the rational level with the emotional. And the same goes for adults. When I go to some panel discussion and play my recordings, the facts about biodiversity, about what is really happening to the planet, touch the people on an emotional level.

For example, I play a sample from the wetlands of Knížecí forest — there are beautiful choruses of the moor frog, which needs water and other particular conditions to live and reproduce. And I show how rich and strong was the vocalization when there was a lot of water in the moor, and then two years later, after the water table significantly receded. The chorus was suddenly much weaker.

You’re working across various fields and disciplines. Do you categorize yourself in any way?

I am absolutely enamored with people from the art scene. The greatest reward for me is the fact that someone is at all interested in these things. And I think that people from this field are extremely open, free of rigid musical schemas and a priori categories. Their perspective is extremely inspiring for me. I feel like a fish in water among them.

You’ve created the Soundscape platform. What is it, how does it work and what are some of its objectives?

I told myself I wanted to research how a particular, geographically defined spot sounds. I decided to take a relatively manageable space of the South Moravian region, which is of course quite large to ever really capture perfectly. But it is interesting in that we have the beginnings of the Vysočina Highlands Region, the White Carpathians, and there is also the lowest point of altitude at the confluence of the Morava and Dyje rivers. And I wanted a person clicking their mouse to be able to compare how these places sound. The sound of these biotopes is ultimately defined by many different factors. The platform focuses on the fauna, but in the future I would like to expand to regions which relate to anthrophony. It functions in a way that if anyone sends me a recording, I am glad to upload it. So far, I have just two contributors. It is not really a large network of collaborators, but the website offers the opportunity for others to take part, and I am able to provide the technical support for that.

There are many opportunities in this field. For example, Filip Johánek rather focuses on the sounding city, which is also fascinating. And Miloš Vojtěchovský has a great project which focuses on the sounds of Prague, and he uploaded some great recordings there recently. I just received a nice letter from a woman in Canada who has recorded cities around the world, asking whether I also go to Šumava, telling me she knows the region and is fascinated by it.

Is the south Moravian soundscape in any way specific?

Each place sounds different, and each individual place sounds different at different times. But since you ask, we can say southern Moravia is typical for its low-altitude sunny places, meandering rivers and wetlands, and its, at least so far, high water table. This generates a spectrum of amphibians and birds which reside here. Historically, Židlochovice has one of the most important localities for the European bee-eater at Výhoň. The people of Židlochovice fondly remember the days when they looked forward to the bee-eaters coming, as they have a specific call. It was, and still is, a bit of an acoustic mark of the locale. Soutok, the place of confluence which I’ve already mentioned, also has its own acoustic specificity, even under the water. Subaquatic sounds are a chapter all of their own. Two weeks ago, I managed to record a very interesting series of worlds which exist underneath the Kyjovka river. These are beautiful acoustic structures which I can listen to for hours at a time, without ever hitting the Record button. It is very calming in that way. But in this particular case I did record it, and I think it’s in fact the first subaquatic recording from this area. I was lucky in that the water insects were very active at that moment. Insects that are active during the night are also interesting — the grand choirs of oecanthus pellucens. With the general environmental warming, its habitat has been expanding northward, and I recently heard it calling even in the Žižkov neighborhood of Prague. Discovering these hidden worlds of sensitive organisms which seem to be telling us something is very alluring.

You mentioned Skupina. What is it and what do you do?

Skupina was founded by Ján Solčani and Filip Johánek, and eventually we met somewhere and they invited me to become a member, which was indeed very nice of them. Skupina has organized a few meetings and events in the space Praha v Brně, where people who are into field recordings used to meet. It was a community of about fifty people, where some were still considering starting to record, while others were already active field recordists. Skupina released some ten albums, two of them mine. Last August, Ján released the Portuguese trio Sublumia who also focus on the acoustic textures of water. And Filip Johánek does interesting sound projects with his students. We are currently planning a joint evening of Skupina. We also want to do something in the space Husa na Provázku, where so far we haven’t been able to due to Covid. Skupina is in the same situation as all of the cultural workers.

Skupina aims to draw attention to the theme of acoustics, work with field recordings, develop a culture of sound recordings, present works in this field, and not only that of its own members. I think it is partly a platform for meeting, partly artistic activity; not very activist, but rather active.

You are also connected to CENSE (Cross European Network for Sonic Ecologies).

CENSE was formed at a conference in Budapest in 2018. Miloš Vojtěchovský called me, asking whether I didn’t want to come along and contribute. It was organized by Csaba Hajnóczy, and the conference’s objective was to form a network which would bring together people interested in similar themes across Europe and thus create an international organization similar to the one already active in Canada. This group mostly presents itself by means of its members’ activities, and each one tends towards slightly different things. Some prefer to write, while others work in sound art, while others still do similar things to what I do. I find it cool that people work on the same activities, projects, support each other and stay in contact. The last event was the global project Reveil of the English collective SoundCamp, which has been organizing a global dawn listening session for eight years in a row now. It begins in London, and as the whole planet is waking up, there are broadcasts from individual sound tents, and this is picked up by British and global radios. We then all stream from our chosen places. And now we added something else to this: one of the Romanian participants of CENSE, the sound artist and friend Anamaria Pravicencu, mixed all the recordings and put them in order as an album. It will be about a two-hour broadcast, and Framework radio program has already shown interest. Framework is, for me, perhaps the world’s foremost radio program focusing on field recordings.

I have yet another project as part of the streaming. It’s not connected directly to CENSE, but with Radio Aporee, a platform run by Udo Noll. Last year, I was invited to the Ponava Café festival in Brno by Tomáš Vtípil, where I recorded the dawn chorus. I was fascinated by the sound of the Lužánecký park and its surroundings. It is beautiful to see Lužánky waking up, in the very middle of the city, with the trams starting to run in the early morning. Noll, who is an expert on field recordings and internet applications, constructed a device and I installed it in Ponava, and its microphones record the sounds of the environment. It has been running nonstop since March. I sometimes play the stream, and it is especially beautiful in the morning. You can play it through the Locus Sonus app. You can see all the other places from which people are streaming on a map.

You are the deputy mayor of Židlochovice. Does your artistic work at all impact this occupation?

Definitely. I am glad that Jan Vitula, the mayor, and I are on the same wavelength regarding the environment, greenery, and the benefit of water in the landscape. We are currently arranging the buying, exchanging and selling of real estate in order to expand the bodies of water at the edge of town. There used to be dead soil, pesticides, chemicals, airborne dust, and all kinds of other things. Today, there is beautiful wetland. Another thing we wish to do is make a canal to the Svratka River. The river would spill out there, which might lure birds, increasing biodiversity, and the whole space would improve. Židlochovice is one of the sunniest places in all of Czechia and we used to have a problem with airborne dust particles. I realize that we are not changing things only physically, but that we are also creating soundscapes where people come to relax. There is also a general problem with acoustic pollution. Because of my interest in acoustic ecology, I can also sometimes use my findings as part of the debates at the municipal board. I am lucky that we have deputies who are glad to lead a constructive dialogue. I am very grateful for that.

What is the culture in Židlochovice like?

Much like many other towns during the pandemic, Židlochovice didn’t have much of a cultural life, because we couldn’t. But we try to keep culture alive in the sense that we preserve and build on local history. We have been organizing festivals at our chateau for a long time, and for the last eight years we have been organizing an apricot harvest festival. Židlochovice is a land of apricots, and we want to show it as such. We of course also stage various events much like in other cities, but we also try to feature some alternative culture. We had, for example, Lenka Dusilová, Eva Turnová came a few times, and Vladimír Merta came for the anniversary of the November revolution.

Small farmers can sell their produce at farmers markets which we regularly organize. We give space also to a wide range of smaller events which have a rather communal character, like greeting the morning birdsong with an ornithologist, or creating nesting places for the bee-eaters. These small, family-oriented and community events are a great boon to the city. Associations are also important for us, and they organize their own events, which we try to support as much as we can.

Can culture play an important role in community life and in resolving social and ecological problems?

Certainly. Everyone is very close here, and the question is whether you use this to your advantage. For example, my wife founded a center for mothers called Robátko, and it has become a tremendous community of people. Say you teach English and are at home on maternity leave, you can teach it to other kids in the center. Or if you are a speech therapist, you can do that. When the people mutually inspire each other and help each other out, that’s how a natural structure of relations is formed. About ten years ago, my wife also worked out a project for the planting and sponsoring of trees, and the ornithologist Pavel Forejtek gave lectures on birds for the local gardening community. And my job and joyful responsibility is to create the conditions for such meetings, where these people can organically meet and inspire each other, and get mutual enjoyment from it.

This is the first of a series of interviews with artists, cultural managers and initiatives published as part of the working process of the project Cartography of (Eco)systems: RurArtMap and Perpedian Map Black Edition. It is a continuation of our efforts in creating the Perpedian Map, in which we present profiles, overviews, and articles describing some of the smaller cultural initiatives in the regions of the Czech Republic.

This project is supported by the peoples of Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway through the EEA Grants.