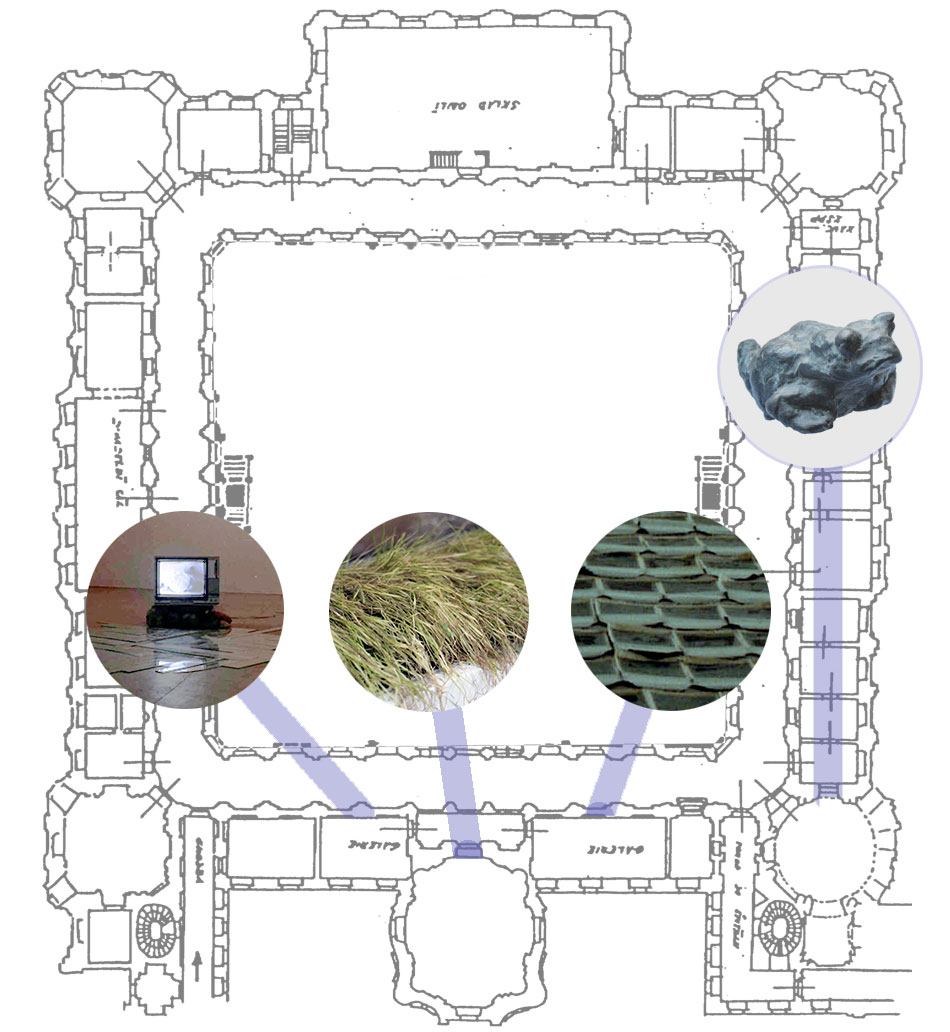

Martin Zet: Altogether: A contemplation (oats, Polaroid reversals, book, sound, hope, fear and video)

The opening took place on 5 May, 1995, with a performance by Alex Švamberk and a concert by Tonton Macoutes.

When you provide

a whole house,

I express

the whole

world.(Book of Sighs, 14 August, 2017)

Altogether (Všeckomožný)

A contemplation in 5 parts:

· 90 minutes, video with sound, TV monitor, boulders, mirrors

· Oats growing on the altar of the Chapel of Saint Benedict, an intervention

· Frescos in the Chapel of Saint Bernard sonified by a chorus of marsh frogs (Pelophylax ridibundus),

· The Sea, 4000 Polaroid reversals of passport photographs, an installation

· Kids, self and Altogether recorded by Martin Zet, a book

The sound of frogs praise the spring behind the fresco of St. Bernard in the chapel. In the room to the left of the St. Benedikt chapel, thousands of reverse Polaroid portraits gaze through the ceiling at the lens of the sky (my first contrapicado), a magnifying glass heats them in a floating beam of light, lifting the Polaroids in a wave. Opposite, every stone and brick of the corridor resonates with the looping hum of a repeating cremation, the colors shattered by mirrors — negative, the positive drone.

Oats sprout on the Benedictine altar. They grow, wither, and then we (Miloš and I) take them outside to merge with the grass under the apple trees. Four years later, the last time I was in Plasy, they were still there.

The eponymous book (prepared by Martin Busta at Dragon Press) was given away on 5 May, 1995. A friend from Marxova Street, Jožka Kunc, arrived with Eva in his Velorex car, a naked Alex Švamberk with the band Tonton Macoutes sampled the voices of frogs that I brought from the National Museum Shop. Jan Brichcín, who, with Vašek Hron, helped prepare the video, shot documentary footage.

M.Z., 17 August, 2017

Interview

RS When did you come first time to Plasy?

MZ In 1993, with Igor Hlavinka. And the first person I talked to at Plasy was Gert de Ruijter, and we’re friends to this day.

RS Igor invited you there?

MZ He told me to come with him – he had been going there since the beginning. I had also heard about Plasy in 1992.

RS Where did you hear about it?

MZ Someone – maybe it was actually Igor – told me that there’s something interesting happening there, but at the same time some friends and I were holding the third (and final) year of the international Granary / Špejchar symposium in Křešice. In 1993, I started to look around to see what else was going on .

RS So, that was 1993, and then did you go there regularly, or did you work there regularly, or go to the openings?

MZ I went when I could, because I really liked it there. Some things I took part it in, others I only went to watch. Sometimes I went to visit the organisers – Martina Tomášková, Miloš Vojtěchovský.

RS Why do you think people considered Plasy important?

MZ It didn’t occur to me that it was important until it ended or afterwards. . I definitely didn’t go there because it was ‘important’ for my career or in some sort of practical sense. I went because it felt good to be there and because I liked the people that were organising the event. . The sense that it was something important came only after I had the opportunity to compare it with other experiences at other locations. That was when you realised it was really something different. Even that place, from the beginning that combination with the location, that’s what made from the event something extraordinary.

RS You said that later you had the opportunity to compare – can you recall the places you could compare it to?

MZ You could compare it, say, to Schrattenberg in Austria.1 It is also relatively open there, but at Plasy it wasn’t necessary for everyone to do something. That was nice about Plasy, that the “artistic production” wasn’t the primary thing. Things were always being created – individual motivation always pushed participants to do something. But if someone decided not to do anything, that was ok as well. It was more of a gathering of people. The event organised by Biljana Petrovska-Isijanin in Bitola, Macedonia, was also important to me.2 It wasn’t tied to one particular building or complex; the plan we got covered the entire small city. It was more intimate, with fewer people and a shorter schedule. In terms of meeting people, my residence at Art Omi3 upstate New York was of key importance to me. There I met someone who came from even further east in Europe than I did: the Lithuanian Redas Diržys, with whom I’ve talked a lot with since then.

RS What did you specifically do at Plasy? Or, if you can recall, what was interesting to you?

MZ Everything there was interesting to me. And what did I do there? From the stone marking the centre of the garth (Subterranean waters / Podzemní vody, 1995) to making tea. Miloš also offered me the opportunity to do my own solo installation in the main monastery building (Alltogether / Všeckomožný, 1995), which became a major turning point for me.

RS What effect did the monastery’s architecture have on you?

MZ It’s a mix of good and bad. It is stunning, grand, and yet diabolical, you can get... strange feelings there. The origins of the site are strange – the monastery was surrounded by swamps, which are traditionally connected with evil forces. And those Cistercians launched their evangelization of the region there, and not always in the humblest of manners.4 Yesterday I was in Opava, where there is a ‘co-cathedral’5 built by the Knights Templar. It is grand, beautiful architecture, terribly tall, but I don’t know why it is here in our country. Perhaps in Italy, where it is warm, large space means something different, but in this country and in most of Europe a large space means cold. In the Orthodox Church, most temples, except perhaps the new Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, are cozy, tiny buildings, mysterious in certain pleasant sense. And even if there isn’t much light there, you feel the warmth. And there is usually the lovely scent of beeswax. But here you enter a huge, cold space, decorated to certain degree. Why do we need this?

But Plasy...To this day I can’t understand it. Everyone tried to be more than just a part of the Czech scene, but if you only need to take two steps to meet interesting people... I don't know, we are investing lot of energy and developing crazy activities to be able to go somewhere else… Maybe it’s because people were “imported” here back then, and so foreigners lost their “appeal”. When there is an exhibition of someone ‘from the outside’ here, I often won’t go. But if I’m ‘outside’, I’ll go have a look. It's such a strange division: when I feel that it's easier, I forget it, but when I'm ‘outside’ I'm more open, more curious. Or, at home, I have a lot of small duties, things to do, things I haven't done, and then I have no time for important things. It’s also true that when I came to Plasy for the first time, I didn’t know what was going on, what to look for, how to find my bearings. Usually you arrive somewhere, you take a look around and you have a rough idea of what’s going on; the exchange of information is complete and there is no need to deal with it any further. Here in Plasy, I couldn't actually say that I knew what it was about until the last moment... (laughs) and I don't even know until today... It's on some different plane of thought, when I don't have anything to do I don't need to sit and wonder what Plasy was actually about. Somehow it was there, somehow it happened. Perhaps someday I will, but right now I don’t have any need to analyse and work out some verbal justification.

RS Nevertheless, this conversation began with you saying that Plasy was interesting for its combination of place and people.

MZ Yes, the place is powerful. But people are more important. And when people gather at an interesting place, the experience is enhanced. But even a boring place can be important. It’s enough when somebody stars making things somewhere, and the place starts to be attractive. So now you’re going to ask why exactly here, right? (laughing)... Miloš is always creating special site-specific situations around him. When Plasy ended, there came Jelení Gallery. He’s a person with a gift, even perhaps a damnation to do community projects. But there were others as well there who sacrificed part of their lives for the situation. . … MZ It's actually interesting: when you really want me to talk about it, I’m all the more inclined not to. The whole thing is beyond-verbal level, and when you start talking about it, it sounds stupid. But that doesn’t mean Plasy should be turned into some 1990s taboo. I just don’t want to search for definitions. And when I do, it’s to accommodate your wishes. I don’t have any need to define it, There’s been a generational change, so it’s different now, but it used to be that whenever I went somewhere abroad and said I was from Czechia, they would ask me if I know Plasy. Today, neither the topic nor site specific are focused on historical buildings. But it once resonated among the generation in their 40s and 50s . What is undoubtedly important is that Plasy wasn’t primarily focused on the visual arts but on the interconnection of different artistic disciplines: sound, music, light, dance, movement. These were present, sometimes even dominant there. It was definitely not exclusively or even primarily about visual art. (Snippets from Radka Schmelzová’s interview with Martin Zet, Masaryk Station, Prague, 4 May 2007, 7:30 a.m.edited by Miloš Vojtěchovský, 2023).

Foto: Martin Zet, photo Daniel Šperl, 1995

1 The artistic residence project was founded in 1990 by Heimo Wallner in the Styrian village of Schrattenberg, where a building was rented from Prince Karel Schwarzenberg. Czechs and Slovaks were frequent guests in the first years. Marian Palla came up with the name Hotel Pupik (Hotel Navel). See http://www.hotelpupik.org/

2 The ‘Elementi’ art group was founded in 1992 by its core members Biljana Petrovska Isijanin and Ljupcho Spirovski Isijanin and several other members who occasionally joined the group in 1992–1997 (Goran Todorovski, Srebre Velikiceski and Kateřina Hristovska).

3 Alumni Art Omi International Artist Residency ,http://www.artomi.org/23/5/2007

4 Editor's note:Most Cistercian abbeys were built on swamps in remote valleys far from cities and populated areas. This isolation and need for self-sustainability bred an innovativeness. Many Cistercian monasteries display early examples of hydraulic engineering and waterwheels. To build on fertile soil was prohibited.

5 Author’s note: If a bishop has two seats, the second is called a ‘co-cathedral’.

Martin Zet (*1959) is a Czech artist and academically trained sculptor who works with the medium of drawing, photo and video and is known also for happenings. His work deals with time in a dual way, time as a course related to durational and destructional point, and time as a trace of memory or the past.