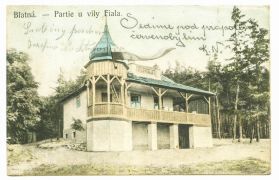

The hill of Vinice (“Vinyard”) rises just beyond the outskirts of the village of Blatná, and atop that hill there was once a pub. The pub was a popular destination for day trips, and was designed by architect Karel Fiala for his brother Theodor, who was a well established citizen of Blatná and also the pub’s owner. He had it built in 1906, and called it a “buffet.” There was a bowling alley, and live music on Sundays. The year 2016, that is one hundred and ten years since, marks the beginning of Pavla Váňová-Černochová’s battle for very existence of the site.

Agosto Foundation: Is it called the Fiala Villa then, or rather Krčkovna?

Pavla Váňová-Černochová: The Fiala Villa is its official name, but until 2016, it was regularly called Krčkovna, also in the official municipal documentation. At the same time however, it was a local, almost pejorative, term. The last Mr. Krček lived a non-conformist life, and hosted many parties. In 2004, the decrepit structure was bought by the city from the bankruptcy trustee, and the neglected house had since been inhabited by drug addicts and the homeless. It was common knowledge that “only weird people go there.”

How did the whole story begin?

In September 2016, I saw a municipal bulletin board which advertized Krčkovna for sale. At that time, I was preparing myself for a tender to the local cultural center, and I had read up extensively on the city’s strategic documentation. I saw that Krčkovna was being sold, along with its adjacent land, for three million CZK which immediately struck me as strange, because the documentation revealed that a municipal park and look-out tower were supposed to be put there. I was thinking, why we are getting rid of half a hectare and a nice building, when we need, for example, a kindergarten? So I went to the mayor…

At that time you had no idea that it was, in fact, a valuable building by the architect Fiala?

I did not. No one really knew. But gradually, I understood that my father personally knew the last Krček, as both were beekeepers, and the story started falling into place on a personal level, too. Finally, my hunch was confirmed by the local historian and the former middle school teacher, Mr. Jiří Sekera, MA. I later found the blueprints in the district archives in Strakonice, and then I went to Prague to the Prague Castle archives. At that time, Petr Měchura had successfully finished a dissertation on the conservation of the Prague Castle during the era of TGM, and a large part of his work was also devoted to Fiala. And so it began. I loved delving into the research.

What happened next?

We wrote the municipality requesting the building not be sold, that it was in fact an important landmark, even on an international level. We corresponded with fifteen representatives. That was the beginning of our “non-communication.” The mayor somehow was offended by our course of action. We subsequently organized a guided tour for the public. Then we wrote four requests about renting out the villa – three have already been rejected, while the fourth will be discussed at “the municipal level” in January, 2019. I generally get the feeling that they are trying to present us as naive idiots who don’t understand anything. I decided to turn to the Department for the Care of Monuments (NPÚ). We set up a meeting at the villa and were flabbergasted! We found it to be, in fact, a beautiful building whose interiors were completely intact, including the wall frescoes. That was December, 2016, and I was excited that I had discovered a historical landmark.

How did the town hall and its representatives initially respond?

Town Hall was not very pleased, as we most likely put the brakes on a pre-arranged sale to a certain influential resident who wanted to tear down the villa and build a wooden structure in its place. The attractiveness of the property lies in its beautiful view of Blatná. As soon as the process of making it a cultural landmark was underway, Town Hall reneged on its intention to sell it. They didn’t even allow us to enter the premises because it was being set up for a building survey. Later, we requested to hold a public event there – Ukliďme Česko (Let’s Clean Up Czechia). Immediately a fence went up and our application was denied. This June, we organized a sit-in picnic in front of the villa and were subjected to an awkward and completely unnecessary sting from the local police.

The villa has received the status of a cultural landmark then?

It still remains undecided. In March, 2018, the Ministry of Culture decided affirmatively. The jury included also Mr. Benjamin Fragner. The municipality, on the other hand, was against the whole process, and eventually were also opposed to it in their statement. Before the September elections, Minister Staněk decided to support that statement, overturned the original decision, and brought everything back to square one, to begin at the phase of assembling documentation. Unless some political authority intervenes, the Fiala villa should be granted the status of a cultural landmark. The building is standing, and is dry…

If it is granted, what would that mean for the villa?

The city will be legally responsible for taking care of it, and they might opt to sell it again. We, the citizens, can only protest and demand we be permitted to take care of the building. We will show that we can fundraise, issue grants and fill its program with activities for the public. Such a concept, however, faces opposition and likely rejection by the councilors.

Are the Town Hall’s actions motivated by ignorance, or lack of experience?

I don’t know. They either don’t want it to happen, or they are inexperienced. In 2017, we gave a lecture on what landmarks are and what we can do to preserve them. I invited Roman Černík from Pilsen’s Moving Station, who managed to save and renovate a train station, eventually making it into a functioning cultural center. And Jana Gajová also came – she is the person behind the successful project Tančírna v Račím Údolí in Rychlebské mountains. Theirs was a similar story to ours: a wooden building which dates to about the same time period. We invited all the councilors to the event, but no one came.

How will you make use of the financial support form the Agosto Foundation?

The Perpedes Grant from the Agosto Foundation is a great help to us. We want to use it to foster better communication with the general public, and develop a simple campaign. Many people don’t have any information about the Fiala Villa, so they can’t develop a personal opinion about it. Some are in fact afraid of us. Rumors are spreading at an alarming rate. “What does Pavla really want to do there?” They often completely misunderstand our motivations. It might be a question of using the right language, as some people are unfortunately sensitive to phrases like “public interest,” “civil society,” “non-governmental organization” and the like. Furthermore, the councilors think about property upkeep in wholly different terms. They do not believe, or lack the experience, that cooperation between an NGO and the municipality can in fact work. They maybe imagine that there might come a point when they will have to use millions of crowns from their budget, but for some reason don’t want an NGO to do it for them. That is why we are organizing programs about these topics – I just hope that the councilors and officials will make time to actually come. They see the only course of action in putting the villa under the auspices of the Center for Culture and Education, but the Center’s employees clearly stated that they are not interested in caring for it, as they have enough work of their own as it is.

Do you ever ask yourself why you do it?

I am genuinely interested in it, and I also enjoy it. Thanks to the Fiala villa, I have met wonderful people and experts. Doctor Měchura, Klára Salzmann, a landscape architect, a teacher from the Prague Technical University, and Mr. Jaromír Beneš, the paleobotanist from the University of South Bohemia – we connected with other projects, with my colleagues from the educational department of the National Gallery in Prague where I used to work. And we have also established many friendships with the locals here in Blatná. All of them are very much on our side and appreciate our work. Cultural work is simply my field, and I have been doing this for twenty years. I enjoy working for my city, organizing lectures and events for the public. It can be done without official support, but it becomes very difficult. Basically, there are two of us doing it – me and my husband. And it is difficult. But there aren’t that many things in life which are meaningful and worth the effort…

What has this battle for saving the building taught you about yourself and society?

Well … we often say to each other at home that the state system is in fact set up well. There exists a number of options which the citizen can use to make themselves heard, whether it is watching over public affairs, or voicing grievances, or just trying to be better informed. For example, law number 106, which plagues our opponents so very much (laughs). Thanks to this law, we have arranged for the Town Hall meetings to be made public on the city’s website.

What kind of events do you organize?

We do events which are not supported by the city about once a month. We had, for example, Olin Bistřický from the NG, speaking about Jože Plečnik. In 2017, we organized a march through the city with a theatrical performance called Blatná 1906 – we walked from the town center towards Vinice hill and the Fiala villa. Then in December we made an excursion to see the Obnova pražského hradu (Prague Castle Renewed) 1919-1938 exhibition in Prague, which was predominantly about Karel Fiala. And last year, we started operating a non-traditional gallery in public space, specifically a train station, which was called the Sedmá kolej (Seventh Track) gallery. Starting in February 2019, we will again organize monthly lectures – we’ve already invited city architect Šimon Vojtík, Mr. doc. Jaromír Beneš and Dr. Žlebčík from Průhonice, who will speak about Blatná’s roses.

What, in your opinion, would be an optimal future for the Fiala villa?

The building should have the status of a cultural landmark, and should be cared for accordingly. It is historically unique and has historical and urbanist value. It is on the park’s property; in fact the park is the very reason for it being built there 113 years ago – so that people could take walks there. And it is amazing that it has remained in such good condition to this day. At least during the main tourist season, it should offer refreshment – food, a small café, a space to rest and for children to play, and the large yard should offer a gradual segue from the forest into the suburbs. There is a beautiful view on the whole town from the terrace. There is also space for simple, community-oriented cultural programs, which could remind people of the house’s architect Karel Fiala who also built the Prague castle and was born in Blatná, or Jan Böhm who was Blatná’s rose gardener and who became world-renowned. And how else to remind outselves of the life of a rose gardener, than with a rose garden? Blatná used to be called “the city of roses“ but still does not have a rosarium. Apart from the dance hall in Račí údolí, our main inspiration comes from the successful Žďár v Chudenicích compound, where there is a look-out tower, a pub, and an arborium. If they can do it in Chudenice, why not here in Blatná?

Can you describe what the operation of the building was like before the First World War?

At the time, in 1906, the Fiala villa stood just outside of town, about twenty minutes by foot through the fields and lake country. It stood on a partly forested hill called Vinice, which also had two orchards. Other buildings along this way from the town’s center were built later. People came here for their Sunday walks, drank coffee, tea, and enjoyed the view of the city, as can be seen on one old postcard from 1910. Blatná also has a long tradition of bowling, and the pub U Fialů also had a bowling alley built next to the villa on Vinice. So people could go bowling anytime, and on Sunday there was live music.

How long was the so-called “buffet” in operation?

The publican Teodor Fiala received the concession in 1905, and the house was built one year later. The town chronicle mentions that there was a fireworks display organized there in 1914, so the pub was in operation at least until then. After the census in 1921, it was used for living purposes. Although no-one remembers those exact times anymore, seniors still reminisce about the house being often visited by various people, so this tradition of hospitality continued on, even after the restaurant no longer functioned.

Does Blatná somehow develop the legacy of Jan Böhm?

Jan Böhm is one of the most important figures of the 20th century for Blatná. He was a world-renowned rose-grower and botanist. His legacy lives on in the Blatná villa which takes his name, and there is also a street named after him. But that is about it. “The city of roses,” as Blatná was called during the First Republic era, does not have its own rose garden, a rosarium. And that is a shame. A place like Vinice would be ideal – there is a wooded park, the historical building of the Fiala villa, and its neighboring garden facing onto the south. The garden has even retained its terraces. We consulted about it with a number of specialists, gardeners, and landscape historians, and everyone was excited about the idea of setting up a rosarium. Blatná and Jan Böhm both deserve it.

You’ve said that one could write a great piece on Jan Böhm, as his story has not yet been researched.

That’s true. Jan Böhm came to Blatná in 1919 and started growing roses here. This struck the other gardeners as funny, trying to grow roses in this raw, rocky land, but Böhm persevered and finally succeeded. He used the wild-growing rose hips for support, and in ten years he had a prospering company. He not only grew the roses, but also bred them. However, he always provided space for smaller breeders by, for example, advertising their produce in his catalogues. In the 30s, he had one of the biggest companies specializing in roses in the whole world. He shipped seedlings, as well as cut roses, to state offices and embassies in Prague, but also to America, Africa, and Europe. At that point, Blatná started to be called the “city of roses,” and it was said that when the wind was coming in from the west, the multi-hectare plantations would perfume the whole city. He managed to grow a million seedlings a year. In 1924, he started to organize rose exhibitions in Blatná, and the one in 1935 was visited also by then-Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mr. Edvard Beneš. The exhibitions were visited by thousands of people. He had the idea to build a rosarium in Blatná where the roses would grow all year, but the war put an end to that.

What is the most remarkable thing about Blatná’s “Baťa of roses” for you personally?

Apart from the fact that he was a very able entrepreneur, he also supported information sharing on the topic of rose breeding. He published articles in magazines, and also informational brochures intended for small growers. He knew that he must support a great product with great advertisement. The names of his roses were related to the Czech nation, naming them after notable living and historical people – Jan Hus, Masaryk, Štefánik, Golden Prague, Mother Nation, Darkness… He also devoted some roses to his family members, like the one called Máňa Böhmová, the Rose-Grower’s Wife… He also pulled off a truly wonderful stunt, in that he cooperated with the film industry in what today would be called “product placement.”

How did he collaborate with the film industry?

In 1934, they shot a romantic movie called Na růžích ustláno (“Bed of Roses”), which was set in a gardening environment. It was directed by Miroslav Cikán, and featured Jindřich Plachta, Antonie Nedošínská and Lída Baarová. Most of the film was shot in the studio, but some of the exteriors were shot in Blatná, including the authentic footage of Böhm’s rose packing facilities and the plantations themselves. One of Böhm’s roses was in fact named Lída Baarová.

And what about his rose-growing business after the war?

Although the war put an end to the dreams of having a rosarium, Jan Böhm tried to continue in his work after the war. But after 1950, his business was nationalized, and then in the 1970s the rose plantations were put under the auspices of the Strakonice municipality. Although it did not reach the popularity it had before the war, the tradition did survive. The plantations were moved to another part of Blatná, and in the 80s, the idea for building a rosarium resurfaced, this time intended for the nearby chateau park. It was ultimately unrealized due to the social changes of following the revolution, after which Blatná’s chateau was returned to private hands. After the Velvet Revolution, the rose business was terminated. However, Jan Böhm’s legacy is rightfully claimed by the wonderful rose-grower Mr. Miloslav Šíp from the nearby town of Skaličany. Maybe it will be successful, and the rosarium in Blatná will finally be realized. Third time’s the charm … and hopefully it will be built at the Fiala Villa on Vinice hill.

Jan Bartoš