Gallery Na shledanou (“The Good-bye Gallery”) is located in the south Bohemian town of Volyně in the Malšička cemetery in a gallery building that was intended to serve as a funeral hall. The gallery focuses on contemporary art with an emphasis on site-specific art as well as the finality of human life. In this interview, Radoslava Schmelzová sits down with curator and art historian and Jan Freiberg to discuss the various challenges and outcomes of the project.

Agosto Foundation (AF): Could you summarize for us the ten years of the Na Shledanou Gallery’s existence? What did those years bring?

Jan Freiberg (JF): Ten years, that’s a long time. Formally, the exhibitions started with mural paintings which were part of the artist residencies we hosted. The reasons for that were largely practical. The gallery, which originally used to be a funeral hall, did not have a concierge, and there was no way we would get the money for it. Also, the number of visitors was not very high at the time. I was working under the assumption that large-format painting would be much more understandable than some other media for the local viewers, who largely weren’t very used to contemporary fine art. So, I chose authors who were working on figurative things which were more easily comprehensible to those who might not follow art regularly. That was the very first stage, about the first two years of our existence.

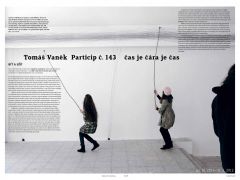

Towards the end of the second year, Tomáš Vaněk, the current rector of the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, did one conceptual thing – a participatory piece through which he wanted to visualize the time one spends in the gallery, and to get the viewers to do the same. One would walk through the gallery with a stick that had a marker on the end. Anyone could join in and make the line thicker. This left a type of ring which spanned the circumference of the gallery, and the viewers left with the experience of walking the gallery, of being there in time and of participating in the creation of a work of art. It was also a test of how more conceptual things presented in a small gallery like ours would resonate with the local public.

Then we featured Martin Zet, the conceptual artist. The work he presented raised some eyebrows with the deputies of Volyně municipal council, as he didn’t exhibit anything at all. In the gallery basement, there used to be a back room with some freezers, and the inside looked like a really decrepit storage space. Zet artistically appropriated a space there which used to be the den of some homeless person. He worked with the theme of a bed as a sculpture, or an object which draws attention to a person’s home and haven. The gallery above remained empty, the author just swept it a bit. And below, there was this great situation which he artistically highlighted. It seemed to be a very socially perceptive piece, but it missed the mark with those who expected art to provide some visual and pleasant experience, something more than just a dirty space. They couldn’t accept the message that Zet’s (non-)exhibition was trying to communicate. This was a certain benchmark which made clear that we often wouldn’t see eye to eye about what is art and what art can do for many of the residents of Volyně.

We then took the path of spatial interventions, where the artists mostly created installations. During its fourth or fifth year of operation, the gallery acquired a certain position on the scene - the program was well conceived, and people from other places started showing up; they were eventually mixed with the locals about one to one.

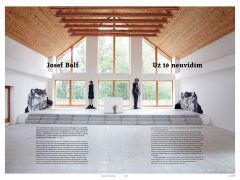

It was at this point that I came to the realization that for contemporary artists, it is difficult to approach the topic of death as perhaps the great mystery. This wasn’t a condition I would impose on the exhibiting artists, but the space itself lead them down that path. The gallery stood next to a dominating cemetery, which kind of spoke for itself. It got to the point when I realized that the works of contemporary artists, ones who had often received great acclaim within the context of secular art, like Josef Bolf, Martin Zet or Tomáš Vaněk, in fact don’t work with material beyond the threshold of our own life. That is also because our dominant culture in the Czech Republic, and vicariously the system of art pedagogy, is mostly secular.

That was also the reason why I approached the architect Norbert Schmidt who works in the studio of Josef Pleskot and is also editor of the theological revue Salve and the director of the Center for Theology and Arts at the Catholic Faculty of Charles University. He is thus an active architect, contemporary art curator at the St. Salvator church in Prague (where Tomáš Halík preaches) as well as a theorist. He follows fine art from the position of the Catholic faith, which in fact has different expectations than secular art. I was interested in how he would approach this theme. His exhibition transformed the space and gave it a burst of energy. However, we finally got into an argument in which I was defending secular thought on art, and I found Norbert’s interpretation to be a bit manipulative. This was of course an interesting moment for both of us, but somewhat unpleasant, so we haven’t seen each other since.

A second important exhibition was prepared by Jiří Zemánek, the historian and art theorist, curator, and activist. All these labels are a bit misleading, but he is simply a tremendously vivacious person who views the world from the perspective of transpersonal psychology, searching for spiritual experiences or different states of consciousness. He believes that we can touch something which lies beyond the threshold of day-to-day life. We could compare this view to that of the Swiss psychologist Carl G. Jung, Anglo-American theorists and practitioners of transpersonal psychology, or the work of the Czech psychiatrist Stanislav Grof who was also interested in alternate states of consciousness. It was important to make exhibitions which would venture beyond the confines of life, but from different positions. Zemánek presented works of a number of artists, as well as prominent texts on poetry, the art of pilgrimage, and different understandings of the cosmos and of the human.

This important milestone gave the gallery a new impetus, but it also remained somewhat misunderstood. I thought it to be quite important within the context of Czech fine art, as works dedicated to similar topics were fairly non-existent. Unfortunately, Volyně is a region which is somewhat interested in cultural centers such as the Na Shledanou Gallery, but still prefers to view them rather as a type of rarity rather than as an important cultural project.

We followed that up with a few ecologically minded events with an often didactic element. Jan Pražan designed silhouettes of birds of prey which we placed on the gallery’s large windows. We had dozens of birds kill themselves on the gallery’s front glass every year. Hundreds of thousands of birds die each year in the Czech Republic as a result of flying into glass panes, but we continue to build more and more glass houses nonetheless. We tried selling those silhouettes as an example of eco-design.

I think an important participatory exhibition was the Tryzna za vakovlka (Funeral for a Thylacinus), which was attended by both artists and the interested public. I asked a number of artists to pick an animal which went extinct in the twentieth century as a result of human activity. All of them then painted extinct animals on the outer walls of the funeral hall, so that the single-species dominance of the cemetery would be somewhat balanced. I wanted to draw attention to the species we had liquidated, and the gallery became a monument to them.

AF: How did your work with virtual reality come about?

JF: It developed from the original intention to create some connection between the museum, where the viewers pick up the keys to the gallery, and the nearby cemetery. It was visualized as an interactive trail which would provide information about the city, museum and the gallery and cemetery. However, the graphic studio which we originally contacted eventually backed out. I then met Vojtěch Rada, a graduate of the architectural studio of Jindřich Přikryl at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague and the sculpture studio of Dominik Lang and Edith Jeřábková at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design, and we decided to do virtual reality.

We present it on a high-end computer and the HTC Vive headset. The experience is not only visual, but also works with balance and with the body. The reason to include VR was also that I was never sure whether the gallery would exist in the long term. It was more or less tolerated but simply remained of marginal interest to the municipality. I came to the conclusion that it would be good to make the events in a place where no one could cancel them, meaning in digital data and digital environments. Being a photographer, I was also interested in virtual reality from the perception of history, as the current discussion on virtual or augmented reality reminds me of the debate which was being had some 160 years ago, when photography became the source of many hopes and dreams, but also of much anxiety. There was also a technological parallel insofar as photography was originally the domain of scientists, due to its technological complexity. Only later did it free itself from technical know-how. And similarly, if we want to do something in virtual reality, we still must be able to program, understand mathematics, etc. Just like photography, virtual and augmented reality will have social and economic impacts.

AF: And how has the work with virtual reality been developing?.

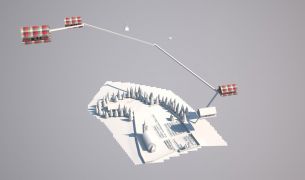

JF: First, we created a corpus of six virtual realities which were intended to render the message of the Na Shledanou Gallery in the virtual medium. We featured the context of the cemetery, the funeral hall and the church. The artistic intervention in virtual reality responded to the previous exhibitions we featured, or went on to create wholly new art works. The most detailed one was Spannugsbogen by Josef Bolf, and then the work of Daniel Vlček who, along with Ewelina Chiu under the name ba:zel, created musical accompaniment for all six parts. Apart from Vojtěch Rada, who was the most important creator of our VR, there was also Klára Fleyberková from Czech Radio, whose voice accompanies the VR experience.

We are also interested in the form of funerary architecture, so Vojtěch Rada and I have been re-creating the Cubist crematorium of Ostrava in virtual reality. It was designed by Vlastislav Hofman along with bridge builder František Mencl (also famous for his design for the Libeň bridge). In Ostrava in the 1920s, they created one of the first crematoria, and which is rightfully considered to be one of the most beautiful Cubist buildings. However, it did not survive, for after many years of lying derelict, it was torn down in 1979. We are working on a story about the construction of crematoria as an architectonic type, of which Ostrava’s former crematorium is an ideal example. Architecture is just one layer, the next layer consists in demonstrating the changes in methods of burial, what meaning cremation had, and what type of religious or social consequences it may have had.

These things were created with me as co-author, but the third project is wholly autonomous. It is currently being prepared by Andrej Boleslavský, a Slovakian digital artist, who is working on a piece about a future which might not be all positive, and it takes place on Mars.

AF: Can you tell us about this year’s festival of virtual reality which took place in Venice, and which you visited?

JF: I am increasingly interested in virtual reality, although the peripheral devices (meaning the computers) are still fairly distant. Augmented reality will arrive, and I am certain that the peripheral devices will eventually not be necessary, and that people will find a way to get the data directly into the brain, without the aid of external devices. In this regard, I think that we are living in a very interesting era, in which we will become ever more entangled with information. I found it interesting to approach this topic from the perspective of art, because from the perspective of technology, we have no mandate there yet.

Apart from the Venice Art Biennale, which featured some two or three works in virtual reality, there is also the Venice Film Biennale, which has, for the third year now, been featuring a festival of virtual reality. It takes place on the island which, in the 15th and 16th centuries, served to confine those suffering from the Plague. A few years ago, they found a huge mass of human bones there, so it is the ideal place for the Na Shledanou Gallery. Some 70 or 80 works were featured there, of which I saw about 40.

Artists are slowly learning how to work with the medium, and it was the first place where I saw some very strong art works/films which the festival’s resources – meaning both in terms of human power and finances – were able to support. These will be able to provide another (parallel) part of our reality.

AF: You co-organized the Prague lecture of curator and virtual reality historian Tina Sauerlaender. Can you tell us a bit about that?

JF: Along with the Czech centers and the Institute of Intermedia, I organized a lecture by Tina Sauerlaender called Virtual Reality in Visual Art. She is a curator of digital art, living partly in Berlin and Vienna, and she has founded numerous platforms which collect data on virtual reality. There are some 100 to 130 works by authors from dozens of countries. Another platform collects the interviews with artists who focus on virtual reality. I think Tina is one of the few curators of all-European, maybe even global, import, who focuses on the art of virtual reality, focusing on its history and its role in contemporary art in general. The lecture took place at an ideal place – the Institute of Intermedia at the Czech Technical University, which tries to connect the technical and artistic spheres.

AF: Let’s go back to the Na Shledanou Gallery. Do you think it has any import in the region as a whole?

JF: About a third to a half of our visitors used to be locals, but we’re not talking about thousands of visitors a year, but rather hundreds. Some exhibitions received great feedback, some remain misunderstood. There developed a unique situation: it is only rarely that a gallery with a strong program remains open for a substantial amount of time out in the rural countryside. I am in this regard also very grateful for the support of the Ministry of Culture. I had great freedom in the conceptions I devised. The museum, with Mr. Karel Skalický as director, made mostly regional art and museum exhibitions. For the local municipal deputies, such a program and institution are more readily understandable, and it provided the gallery some great support, helping it in fact survive. Volyně then saw a large influx of young people who finished their studies, and they were mostly humanities-educated people in their 30s and 40s. They started doing what they were taught to do and have since acquired positions mostly in the sphere of education or local politics. These people would also come regularly to our events. The gallery also influenced the wider region, as I was in contact with people from nearby Prachatice or Strakonice. Students from České Budějovice also used to come. It however also became an important symbol for those people who may have never visited it but were aware of its value and import.

AF: In retrospect, could you have improved something in your communication with the city council, or is this a classic case of coming hard against a certain level of conservatism in the regions?

JF: We should have communicated with them more. We will never know what that may have translated into. Maybe this openness and activity would not have paid off, and the gallery would cease to exist anyway. For those who were in a position of power to decide on its fate, the gallery always remained kind of invisible, which may have been best for its further existence. There was a general sentiment that nothing interesting happens there. The importance of things depends on our ability to discriminate our values. For whomever had a low capacity of discrimination, the place was all but invisible. That was one of the positive aspects of the Na Shledanou Gallery, as it helped to expand the granularity of perception for fine art and disrupt stereotypes. But it also often came hard against those same stereotypes.

Gradually, we started communicating more. It was either through me coming to the council with some project, or I started to go “outside the gallery walls,” trying to change things in the surrounding area: raise a sculpture, open up a vista onto the Šumava mountain range, or implement some games in the environment. I was trying to improve the gallery’s relationship with the proposed housing development downhill from the cemetery, or to dissipate the overwhelming opinion that a cemetery is a place where nothing should ever happen. The council, however, had other plans.

AF: Can you tell us why we have been speaking of the gallery in the past tense?

JF: Towards the end of 2018, some deputies started working towards giving the building its original funerary function. In the spring of 2019, the motion was passed. The architectural proposal was created very quickly, even before the motion was passed in fact. I thus realized that there exists the possibility of receiving some financial sum for the realization, but I never received any official data on its source.

I started intensely negotiating, and I was adamant in my opinion that there is no reason to return to the past, to the spirit of communist-era burial methods, which was the era when this architectonic type of hall was created, meaning the 1950s and 1960s. It was intended to replace sacral architecture at the time.

My opinions also reflected on the periodical Smuteční Noviny (Funerary Times) which we published as part of the gallery’s activities. These issues described in very scientific and informed ways the history and function of funerary architecture. I was trying to protect the gallery’s legacy, which always worked with the theme of death, from being devalued to a mere funerary hall which furthermore had its roots in that atheistic horror house. The construction was however initiated by a local representative of the KSČM (Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia), which meant we did not see eye to eye in our ideological stances. If the other deputies had looked ahead, a different prototype may have been built, a multifunctional space which would reflect the society’s changing needs. These no longer need for funerary buildings being separate from other social events. I did not even insist on the gallery’s continued existence, and the council did not understand that either. They kept promising the possibility of continuation, in parallel with a reconstructed funerary hall, but where art would only have the status of design.

When the negotiations were not leading anywhere, I went to the media, and appealed to the expert community to sign up for support. Just a few days before the final authorization of the project documentation by the city council, I received around twenty signed letters of support. It had no impact on the council’s decision. I also appealed and presented arguments during the proceedings, but it didn’t help anything either.

I assume the city ultimately did not receive the funds, because just now, in early October, the director of Volyně’s museum invited me to discuss what could be the next steps for the gallery. If the city really did want to hold ceremonies for the public there, as it had professed to do, it could have used the 300,000 CZK intended for the project to clean up and adapt the house for improvised ceremonies. One already took place there during the gallery’s existence, with hundreds of people in attendance, and no one complained about the state which the building was in. Unfortunately, there was no intention to hold ceremonies there for the public, but rather to simply receive subsidies for renovation. But that’s of no help to the community who would much rather have nice ceremonies, no matter the place where they might be held. We will see what the future will bring for the Na Shledanou Gallery.

AF: And what will you do professionally without the Na Shledanou Gallery?

JF: I was named director of the František Drtikol Gallery in Příbram where, apart from working with photographs, exhibiting paintings and cultivating the relationship with the interested public, I will also be supporting the development of new art works for virtual reality.

And I have this plan to have sculptures and art interventions in my orchard in Strakonice. They should be an homage to fruit trees, and to create space for experiencing nature and art together. The orchard would, at least initially, remain private and intimate. I am currently discussing this with Jiří Příhoda and Patrik Pelikán. In the first phase, we would create a modern gazebo as a space for the temporary installation of sculptures or for just sitting, and maybe having one sculpture outside it which would ideally be taller than the surrounding ancient trees. In the future, we would like to invite artists for residencies right in the orchard. I consider the option to experience art in the open air as very important for the region’s cultural context.

I am also considering a second, related, but much more demanding project. The municipal council of Strakonice has for a long time been considering allotting an industrial zone right in the orchard’s neighborhood. This project will most likely remain unrealized, or only on a very small scale. There is a number of properties which belong to the city. I would like to expand the orchards and cultural landscape into the surrounding fields and thus create a temporary leisure zone with landscape architecture and art.

The interview with Jan Freiberg was conducted by Radoslava Schmelzová.

Jan Freiberg is a photographer and art curator. He studied photography in the studio of Pavel Baňka at the University of Jan Evangelista Purkyně in Ústí nad Labem and the History of Theory and Design and New Media at the Academy for Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague. He was active as photographer and curator of the exhibitions at Galerie Klatovy/Klenová, and since 2010, he has been curator of the cemetery gallery Na Shledanou in Volyně. He publishes a periodical dealing with the relationship of death, art and architecture. He has collaborated on the project Husákovo 3 + 1 or Oživte si Barák. He is the founder of the Oživme si Strakonice initiative and the projects Sadařství a Fotografie (Aboriculture and Photograhpy).