Common tumbleweed, tumble pigweed, tumbleweed, prostrate pigweed, pigweed amaranth, white amaranth, wind witch, Russian cactus or white pigweed. It is native to Euroasia but in the 1870s, it appeared in South Dakota when flaxseed from Russia turned out to be contaminated with Kali seeds. Although it is the best-known of this group of weeds, and was at first thought to be a single well-defined species, it now is known to have included more than one species plus some hybrids. This has led to taxonomic confusion in dealing with species in the genera Salsola and Kali in America. Recent studies show that the population that once was assigned to Salsola tragus really includes three or more morphologically similar species that differ in flower size and shape. The group was widely assigned to the family Chenopodiaceae – including the genera Kali and Salsola – have since been included in the Amaranthaceae. They now are allocated to the Salsoloideae, a subfamily of the Amaranthaceae.

Tumbleweed is the term commonly used for a number of plants that break off at the base of their roots when they die. Since they’re more or less round and lightweight, they literally dry up and blow away when the first good wind comes along. During tumbleweed season, which is late summer/early fall, they travel for miles through stubble fields, prairies, deserts, and other wide-open spaces.

Most tumbleweeds are actually Russian thistles, and though they’re not true thistles, their branches have that same thorny quality. If two or more tumbleweeds happen to tumble into each other, their barb-covered branches stick to each other like pieces of Velcro. At times they unite into super-weeds that are double or triple in size. Watch out if one of those comes rolling down the highway!

According to plant historians, Russian cactus or thistle, which grows naturally on the steppes of Russia, first appeared in America in the 1870’s. It was introduced in South Dakota by Russian immigrants who unknowingly carried it in their flax seed. When the immigrants planted their first crop, they got flax all right, but tumbleweeds, too.

Within twenty-five years, those hardy weeds had tumbled a thousand miles to the Mexican border, and they now grow in every state in the West. They’re especially plentiful in drier climates where the ground is flat enough for them to move around easily. Though they don’t need much water, they rarely survive in altitudes above 8,000 feet.

It is almost impossible to control because of its huge capacity for producing seeds. One plant can develop up to 50,000 seeds, which fall off as it bounces across the ground. Stubborn as mules, tumbleweeds conserve water like camels to choke out other weeds and grasses, and are often the only plants to survive a draught. Weed killers can be applied to keep tumbleweeds under control, but the noxious plant has spread too far to be wiped out completely.

There’s no Guinness record for the longest journey made by any one tumbleweed, but they can travel great distances. They don’t stop rolling until they run into something blocking their path. Most often this is a fence, where the majority of tumbleweeds come to the end of their trail.

As weed after weed tumbles against a fence, they lock together in a tangled mass that eventually provides shelter for pheasants, quail, rabbits or other small animals looking for a place to hide. Coyotes sneak along these stretches like hungry fence line riders, searching for a meal. Snakes, too, mosey inside for a rodent snack, or to nap in the shade during the heat of the day.

A tumbleweed is a structural part of the above-ground anatomy of a number of species of plants. It is a diaspore that, once mature and dry, detaches from its root or stem and rolls due to the force of the wind. In most such species, the tumbleweed is in effect the entire plant apart from the root system, but in other plants, a hollow fruit or inflorescence might detach instead. Xerophyte tumbleweed species occur most commonly in steppe and arid ecosystems, where frequent wind and the open environment permit rolling without prohibitive obstruction.

Apart from its primary vascular system and roots, the tissues of the tumbleweed structure are dead; their death is functional because it is necessary for the structure to degrade gradually and fall apart so that its seeds or spores can escape during the tumbling, or germinate after the tumbleweed has come to rest in a moist location. In the latter case, many species of tumbleweed open mechanically, releasing their seeds as they swell when they absorb water.

The tumbleweed diaspore disperses seeds, but the tumbleweed strategy is not limited to the seed plants; some species of spore-bearing cryptogams—such as Selaginella—form tumbleweeds, and some fungi that resemble puffballs dry out, break free of their attachments and are similarly tumbled by the wind, dispersing spores as they go.

Apart from its primary vascular system and roots, the tissues of the tumbleweed structure are dead; their death is functional because it is necessary for the structure to degrade gradually and fall apart so that its seeds or spores can escape during the tumbling, or germinate after the tumbleweed has come to rest in a moist location. In the latter case, many species of tumbleweed open mechanically, releasing their seeds as they swell when they absorb water.

The tumbleweed diaspore disperses seeds, but the tumbleweed strategy is not limited to the seed plants; some species of spore-bearing cryptogams—such as Selaginella—form tumbleweeds, and some fungi that resemble puffballs dry out, break free of their attachments and are similarly tumbled by the wind, dispersing spores as they go. Many tumbleweeds establish themselves on broken soil as opportunistic agricultural weeds.

Tumbleweeds have also been observed to cause issues with wastewater treatment plants. In some cases of inadequate fencing, they can get entangled in electromechanical equipment within plants such as clarifiers and mechanical aerators leading to increased energy use and labor cost associated with operating and cleaning the units.

(In Europe, more than 12,000 alien plant and animal species are recorded (DAISIE 2009, www.europe-aliens.org) and the numbers of successfully establishing species con-tinue to grow (Hulme et al. 2009, van Kleunen et al. 2015). Unfortunately, research, legislation, and management of IAS are not fully coordinated, neither within individual countries, nor continentally (Hulme et al. 2009), which leads individual countries to cope with alien species in different ways. The most common approach is based on pro-ducing lists of prominent IAS that receive much attention and are prioritized in terms of prevention, monitoring and management. These so-called Black, Grey and Watch (alert)) (NeoBiota 28: 1–37 (2016)doi: 10.3897/neobiota.28.4824http://neobiota.pensoft.ne)

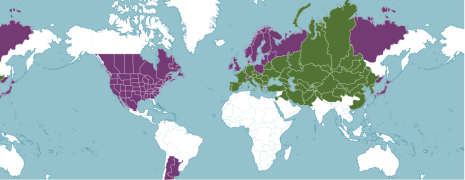

Native to: Afghanistan, Albania, Altay, Austria, Baleares, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, Buryatiya, Central European Rus, China North-Central, China Southeast, Chita, Corse, Czechoslovakia, East European Russia, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Inner Mongolia, Iran, Iraq, Irkutsk, Italy, Kazakhstan, Kirgizstan, Korea, Krasnoyarsk, Kriti, Krym, Manchuria, Mongolia, Netherlands, North Caucasus, Pakistan, Palestine, Portugal, Qinghai, Romania, Sardegna, Sicilia, South European Russi, Spain, Tadzhikistan, Tibet, Transcaucasus, Turkey, Turkey-in-Europe, Turkmenistan, Tuva, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, West Himalaya, West Siberia, Xinjiang, Yugoslavia

Introduced into: Alabama, Alberta, Argentina Northeast, Argentina Northwest, Argentina South, Arizona, Arkansas, Azores, Baltic States, British Columbia, California, Canary Is., Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Denmark, District of Columbia, Finland, Georgia, Great Britain, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Ireland, Japan, Kansas, Kentucky, Labrador, Louisiana, Madeira, Maine, Manitoba, Maryland, Massachusetts, Mexico Northeast, Mexico Northwest, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Brunswick, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Newfoundland, North Carolina, North Dakota, North European Russi, Northwest European R, Norway, Nova Scotia, Ohio, Oklahoma, Ontario, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Poland, Primorye, Prince Edward I., Québec, Rhode I., Saskatchewan, South Carolina, South Dakota, Sweden, Switzerland, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming, Yakutskiya.

(source: Wikipedia)