This invitation is a gift because after a year of research that I and Jovita have undertaken to put together the largest exhibition to date on Slovenian punk and photography, focusing on photography, we can focus precisely on art and history, building a future archive.

The exhibition Slovenski Punk in Fotografija / Slovenian Punk & Photography, opened on December 4, 2023 and runed until January 30, 2024 in the main gallery of the Cankarjev dom, Cultural and Congress Center in Ljubljana, Slovenia, a center that was built in the 1980s as a bastion of modern art, appeared at the same time as punk in Slovenia.

Two worlds apart nevertheless touching each other. Our research work includes the creation of an archive of names1 and works about the punk movement in Slovenia, including punk bands from Rijeka, Croatia. In order to set up such an exhibition, we had to build an archive based on the importance of punk in Slovenia as a rebellious music movement, but also as a protest and criticism of socialist times. Even though punk was always pro-socialist. When we go through numerous authors, their relationship is such that we not only bring them to a point of reflection, but view them through a timeline that implies utopia, heterotopia, and dystopia.

If we want to listen to punk music, we have to listen to images, as Tina Campt's book title says.2 First of all, to compile something like an archive of the 1980s that can only be associated with the punk movement and the underground scene of Ljubljana is a big work. Unlike other former Eastern European countries, this movement shook the status of art and culture under socialism. It began in 1977, two years after the punk movement in Great Britain, where the first punk band took over the ground, streets, and bodies in 1975. The Sex Pistols were screaming against the Queen and her fascist regime in 1975, announcing the coming neoliberal collapse of capitalism, which was in full swing already throughout the last class struggle of the 1980s, and this was not in socialism at the time, but in Britain with the revolt of the miners, their protests, strikes against Thatcher.

So we have the first images of authors from that time, published as early as 1977, to show you how photography became an important archival tool and how photography, first analog and then digital, became a very important memory store under socialism and post-socialism and turbo-socialism, which transitioned into capitalism itself. Especially in this context, so not just any kind of photography and not just any kind of movement, but punk, defined as the last great rock and roll avant-garde movement of a rebellion that was fundamentally social and political intervention in the socialist structure.

That's something special and really makes a big difference for the space of former Yugoslavia as a tampon zone, something that many say is, a false socialist country in between hardcore communism on the East and West capitalism, as well as a country of self-management.

Nothing is beyond temporality, but what is a change is to think temporality differently, i.e. not as past, present, and future, but as something that has to do with utopia, heterotopia, and dystopia. Especially important was that punk, no matter how rebellious it was, was oriented toward a utopian space. At the time it emerged, it was very critical and eccentric, but it was connected to different temporalities, like the work of Tone Stojko, one of the authors who mapped socialism, post-socialism, and so on. In Slovenia, in the former Yugoslavia, it is only in this relationship that it is possible to create this utopia and at the same time to represent the archive of workers' protest. When art represents a collision, it cannot think of an autonomous esthetic, but always in relation to something external, that is political, or social….

At the same time, the utopia on the street passes into the underground of the Ljubljana scene. We see how a heterotopian space is already formed in the 1980s, in the 1990s Miloš speaks of autonomous spaces or zones, for us Foucault's heterotopia jumps directly into post-socialism. Look at the heterotopic space of the Disco Fv 112/15 in 1980, which led to the heterotopia of the 1990s as Metelkova.

1 Positions in the exhibition are: Janez Bogataj, Božidar Dolenc, Vojko Flegar, Dušan Gerlica, Siniša Lopojda, Elena Pečarič, Matija Praznik, Bogo Pretnar, Bojan Radovič, Relations / 25 Years of the Lesbian Group ŠKUC-LL, Mladen Romih, Tone Stojko, Jože Suhadolnik, Jane Štravs, Tožibabe, Igor Vidmar.

2 Tina M. Campt, Listening to Images (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017).

JOVITA PRISTOVŠEK

The utopian imagination has always been very much linked to the long history of social movements and to the idea of the absence of borders, to the implosion of borders in a double sense, in the sense of social processes and in the sense of the abolition of borders in our minds or thoughts.1 As Marina has shown, the 1980s in Slovenia were about breaking through the space of the empty formalist tradition that prevailed until the early 1980s.2 Moreover, it was about the politics of subjectivation, about the production of new subjects, about the question of the subject who will take a different path in a certain space.3

Foucault introduced the “history of spaces” in his 1967 lecture “On Other Spaces.” In this text, which was not published until 1984, Foucault defines (in contrast to the “interior" space) two forms of "exterior" spaces, “that have the curious property of being in relation with all the other sites, but in such a way as to suspect, neutralize, or invert the set of relations that they happen to designate, mirror, or reflect. These spaces, as it were, which are linked with all the others, which however contradict all the other sites, are of two main types”: utopias and heterotopias.4

To make Foucault’s analysis brief: Heterotopia can be a space that juxtaposes several spaces in a single real place, several places incompatible in themselves. It can be a (materialization) of utopia or of an illusion, a reflection of a given order and the source of a new or possible order. It is an "other space," a space of otherness, which is always in relation to the interiority that establishes it, i.e. to power. Here we can also consider Metelkova in the 1990s as a heterotopia, an enacted “utopia.”

What is Metelkova? In addition to the crucial role of the spaces already mentioned by Marina, such as the ŠKUC Gallery, Disko FV, etc., and new social movements such as the pacifist movement and the coming-out movement of gays and lesbians, Metelkova also stands as a "touchstone" for the potential of so-called “civil society” to “sustain democracy” as Slovenia and Ljubljana entered the “transitional period" of the 1990s.

The space itself, which today bears the name Autonomous Cultural Center Metelkova City and is, as is often said, one of the most vibrant cultural, artistic, social and intellectual urban areas of Ljubljana and one of the largest aggregations of alternative and underground cultures in Europe,5 has a very long history: from occupations, nation-state violence, wars, racism, fascism, Nazism to today's neoliberal global capitalism.

The Fourth of July Military Barracks were originally commissioned by the Austro-Hungarian Army in 1882 and completed in 1911. From the end of World War I until 1941, the barracks were used by the army of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (formerly the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes). During the World War II it was occupied by the Italian fascists and then by the German Nazis. From 1945 until the end of June 1991, the area was in the hands of the People's Army of Yugoslavia (JLA).

Therefore, until the outbreak of the Ten-Day War over Slovenia (in June and July 1991), Metelkova had the status of a military complex housing the command of the Yugoslav Army. The latter withdrew from Metelkova in September 1991 after the barracks, like other Yugoslav People’s Army barracks in Slovenia, were cut off from water and electricity supplies.

According to Bratko Bibič, in its initial phase Metelkova had the status of a pilot project for transformation into a “demilitarized zone” and a “socio-cultural ex-center” within the initiatives for gradual demilitarization of Slovenia in the late 1980s and early 1990s (in the period before the outbreak of war in the former Yugoslavia). This coincided with the demilitarization processes that were a direct consequence of the end of the Cold War on both sides of the already fallen Berlin Wall. It also coincided with political efforts to eliminate all military apparatuses within society and in international relations on a global scale.6

After the dissolved agreement with the new generation of underground hardcore punk activists, independent and alternative artistic and activist groups—and let me add that the so-called Committee for Human Rights and Network for Metelkova (1990–96) had already prepared a comprehensive concept, including an organizational and infrastructural program and that these preparations had been underway since 1988—so in 1993, after the terminated agreement on the legal takeover of the Metelkova space and the decision of the Ljubljana City Council to demolish the abandoned military complex, Metelkova was occupied by both the Network for Metelkova and squatters who were not connected with the processes of the Network for Metelkova. The production began immediately, with concerts, theatre performances, round tables, poetry evenings and exhibitions etc.

In the same year, the city of Ljubljana cut off the water and electricity supply in Metelkova. Metelkova is not only an example of the constant threat of demolition and interruption of water and electricity supply. It also demonstrates, perhaps more eloquently but less obviously, the constant pressure of the process of institutionalization and museumization of Metelkova: or, from a wider angle, in Marina’s words, “the processes of expropriation and exhaustion, abstraction and evacuation that are taking place in contemporary art and culture.”7

notes:

1 Achille Mbembe, “The Idea of a Borderless World,” lecture, Yale University, New Haven, Connectut, ZDA, March 28, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NKm6HPCSXDY.

2 Marina Gržinić, “O repolitizaciji umetnosti skozi kontaminacijo” [On the Repoliticisation of Art through Contamination], Filozofski vestnik 26, no. 3 (2005): 118.

3 Ibid.

4 Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” trans. Jay Miskowiec, diacritics 16, no. 1 (spring 1986): 24. Originally published as “Des Espace Autres” [March 1967], Architecture /Mouvement/ Continuité (October 1984).

5 “Metelkova mesto Autonomous Cultural Zone,” culture.si, updated November 11, 2018, https://www.culture.si/en/Metelkova_mesto_Autonomous_Cultural_Zone.

6 Bratko Bibič, Hrup z Metelkove: Tranzicije prostorov in kulture v Ljubljani [Noise from Metelkova: Transitions of Spaces and Culture in Ljubljana] (Ljubljana: Mirovni inštitut, Inštitut za sodobne družbene in politične študije, 2003), 10.

7 Marina Gržinić, “Abstraction, Evacuation of Resistance and Sensualisation of Emptiness,” NeMe, July 9, 2006, https://www.neme.org/texts/abstraction.

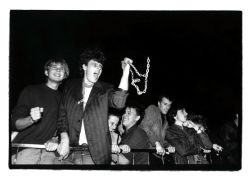

Jane Štravs, Tomaž Hostnik (1961–1982), Laibach, Novi Rock ’82, Ljubljana, 1982. Presented in the exhibition Slovenski punk in fotografija / Slovenian Punk & Photography, curated by Marina Gržinić, December 5, 2023–January 30, 2024, CD Gallery, Ljubljana, Slovenia.

MARINA GRŽINIĆ

These relations refer to the dystopia of the music band Laibach and utopia as the force of the uprising of the LGBT scene in the 1980s in Ljubljana. The idea of a just society, where everyone has a right to basic human rights, to their own identity and dignity, disappeared after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Today, various Orbans, Janšas, etc., speak of a territory, city, or village without LGBTQ persons, which is nothing else than a toxic space of oppression, and again, paradoxically, supported by the former "oppressed socialist men and women.”

On the contrary, punk was an act for the ideals of socialism, the workers, and the ideals of a socialist society, crushing the space of heteronormativity, inequality, and invisibility, as in Jane Štravs' image of the band Borghesia.

Our archive also extends to the present of the last years of the pandemic, from 2020 to 2022.

Jane Štravs, Magnus, Borghesia, Ljubljana, 1984. Presented in the exhibition Slovenski punk in fotografija / Slovenian Punk & Photography, curated by Marina Gržinić, December 5, 2023–January 30, 2024, CD Gallery, Ljubljana, Slovenia.

Just as Orban, as quoted by Miloš, said that we look to the future from the former Eastern Europe, as the West should be this future, writes Miloš, while again referring to Orban that the former Eastern Europe is now a future, I would like to say that, in contrast, we see a gloomy neoliberal totalitarian space of nationalist politicians who extend their power over the future of the former Eastern Europe.

It is a dystopian space of violence and control, not imposed by the West, but embraced by most people in the various nation-states of the former Eastern Europe.

In Slovenia, the future of Europe had disappeared during a pandemic under Janša's regime.

Stojko, the photographer of Slovenian socialist modernity, postmodernity, and globalization, has shown this disappearance through photographs of protesting people on the streets in the times of the pandemic. Therefore, it is paradoxical that in the 1980s, in the midst of black and white photographs about punk and of punk, we also have the color photograph of Siniša Lopojda, showing pastel colors on a black and white photograph, colored by hand. This is a great socialist invention, a utopia.

Siniša Lopojda, Palma, punk evening, Ljubljana, 1987. Presented in the exhibition Slovenski punk in fotografija / Slovenian Punk & Photography, curated by Marina Gržinić, December 5, 2023–January 30, 2024, CD Gallery, Ljubljana, Slovenia.

The colorful mohawk of the punk in the 1987 photo by Lopojda appears paradoxical when we compare it with the 2020 photo by Tone Stojko, taken in times of pandemic. The photo from the 1980s is full of colorful utopia and style, hope. But in 2020, at the time of the pandemic, Ljubljana is seen with a protesting group of people dressed almost entirely in black. The only colorful element in this depressing time is the girl in red (a bit of revolution) that we have been waiting for, and the other is with the slogan, which is clear: “Against dictatorship, against inequality, Janez Janša, fuck off!”

I add that all these authoritarian former Eastern politicians, who sell themselves as liberal, but are exactly the opposite, are right-wing, toxic, violent, neoliberal, and authoritarian.

So we do not care about Orban and his future. We want our future and we will get it!

(photo: Tone Stojko, The First Anti-Government Cycling Protest, Ljubljana, April 24, 2020. Presented in the exhibition Slovenski punk in fotografija / Slovenian Punk & Photography, curated by Marina Gržinić, December 5, 2023–January 30, 2024, CD Gallery, Ljubljana, Slovenia.)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bibič, Bratko. Hrup z Metelkove: Tranzicije prostorov in kulture v Ljubljani [Noise from Metelkova: Transitions of Spaces and Culture in Ljubljana]. Ljubljana: Mirovni inštitut, Inštitut za sodobne družbene in politične študije, 2003.

Campt, Tina M. Listening to Images. Durham: Duke University Press, 2017.

Foucault, Michel. “Of Other Spaces.” Translated by Jay Miskowiec. diacritics 16, no. 1 (spring 1986): 22–27. Originally published as “Des Espace Autres” [March 1967], Architecture /Mouvement/ Continuité (October 1984).

Gržinić, Marina. “Abstraction, Evacuation of Resistance and Sensualisation of Emptiness.” NeMe, July 9, 2006. https://www.neme.org/texts/abstraction.

Gržinić, Marina. “O repolitizaciji umetnosti skozi kontaminacijo” [On the Repoliticisation of Art through Contamination]. Filozofski vestnik 26, no. 3 (2005): 115–131.

Mbembe, Achille. “The Idea of a Borderless World.” Lecture, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, ZDA, March 28, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NKm6HPCSXDY.

“Metelkova mesto Autonomous Cultural Zone.” culture.si, updated November 11, 2018. see: https://www.culture.si/en/Metelkova_mesto_Autonomous_Cultural_Zone.